This 12-Year-Old Created DIY Air Filters That Remove Up to 99% of Airborne Viruses in Classrooms—and Her Idea Is Spreading

I can still picture the first classroom where I saw a homemade air filter humming in the corner. It wasn’t sleek. It wasn’t expensive. It was a simple cube of furnace filters taped around a box fan, decorated with stickers and a crayon drawing of a school mascot. And yet the adults in the room treated it like a quiet little miracle. The teacher said the kids called it “our clean-air machine.” When you understand the story behind it, you start to feel the same way.

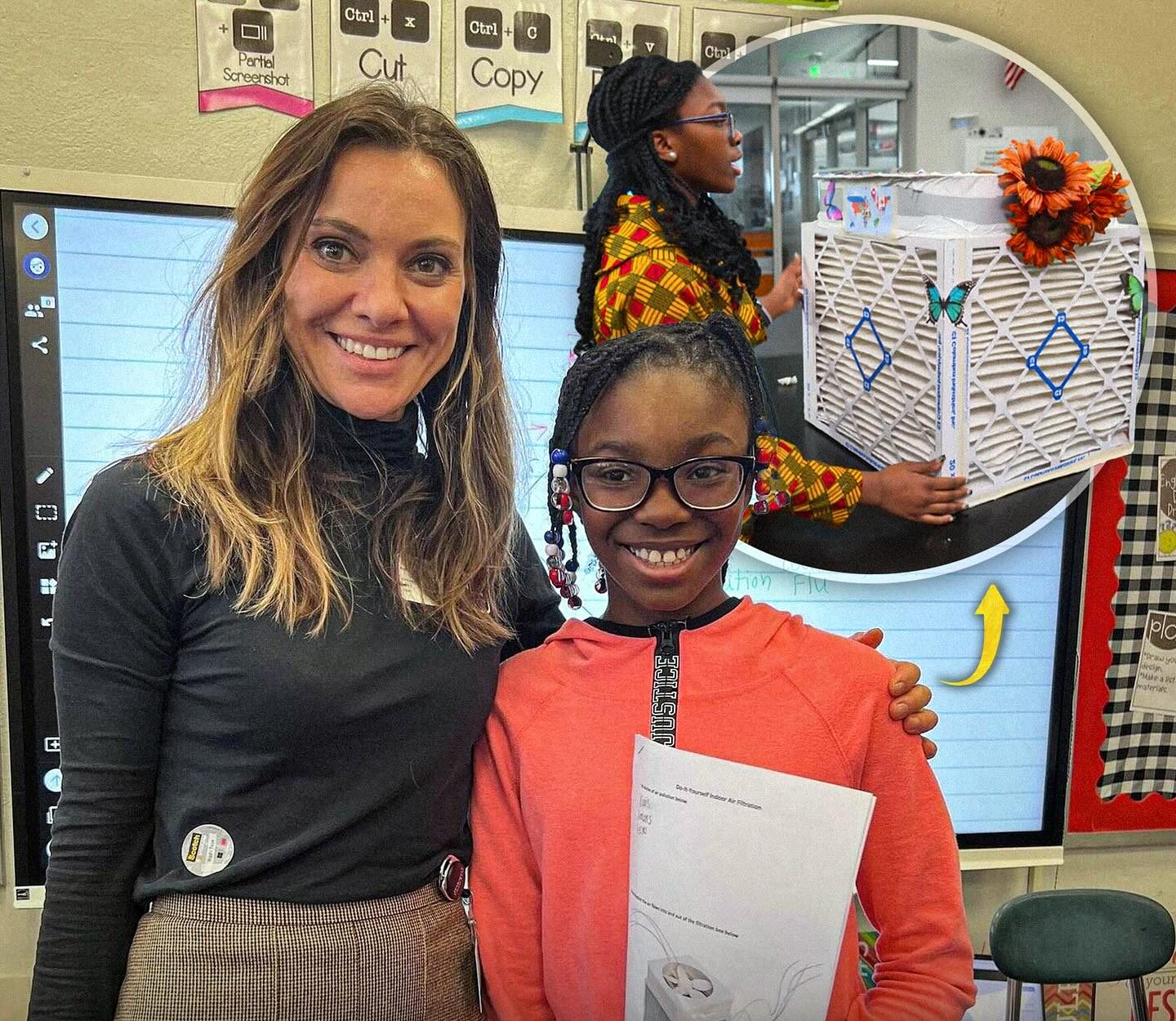

That story begins with a kid—twelve-year-old Eniola Shokunbi from Connecticut—who noticed something most of us brush off. Her classroom felt stuffy. Friends were missing school with coughs and fevers. The building was almost a century old and opening a window in winter wasn’t a plan, it was a wish. So Eniola did what curious kids do: she asked questions, dug into how air moves through a room, and wrote to people who might help. She sent a letter to scientists at the University of Connecticut asking them to come show her class how to build a better way to breathe at school.

That letter turned into a partnership, and the partnership turned into action. With researchers from UConn guiding the work, students assembled a do-it-yourself air purifier known as a Corsi–Rosenthal Box. The idea is charmingly straightforward: you use a standard box fan to pull room air through four or five high-quality furnace filters taped into a cube. Those filters catch the tiny particles that float in the air—dust, smoke, and the aerosols that can carry respiratory viruses. It’s not magic; it’s physics and good filtration. In controlled testing, versions of this device removed over 99% of airborne test viruses in about an hour of operation. That number doesn’t mean you can switch off common sense—ventilation and masking still matter during outbreaks—but it does show how much cleaner the air can get with a few smart materials and a little determination.

I love that the first thing everyone says about these boxes isn’t the percent figure or the airflow rate. It’s the price. A classroom unit can be built for the cost of a field trip lunch—filters, a fan, tape, cardboard—and it works. There’s something beautifully democratic about that. Clean air stops being a luxury add-on you order from a catalog and becomes a weekend project families, teachers, and students can do together. It also becomes a lesson. A student can see the difference on a handheld particle meter and then feel it, too—the room smells less stale, allergies flare less often, and that dull afternoon haze lifts just a little.

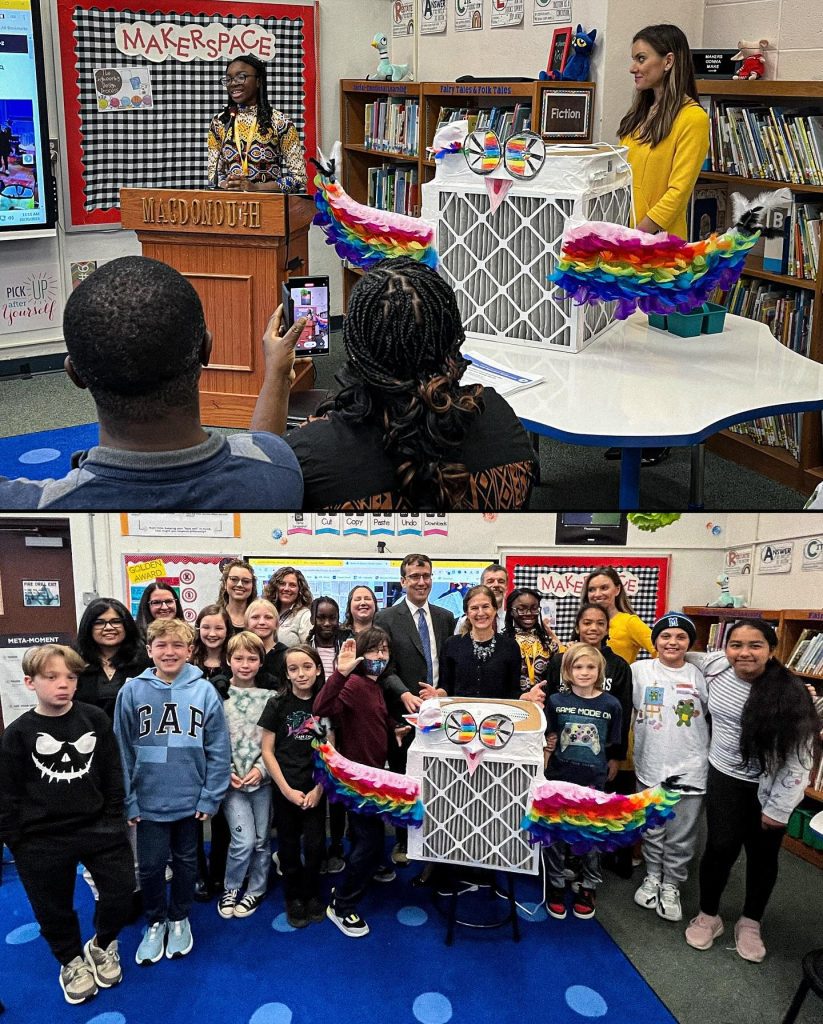

What makes Eniola’s story different is that she didn’t stop with one box. She helped make the case that every classroom in her state deserved the same chance at clean air. Lawmakers listened. Funding followed. Suddenly, there was real support to build and deploy thousands of units, with students playing a part in assembly and even data collection. It’s practical civics wrapped in a science project, the kind of hands-on learning adults remember for decades. I’ve seen photos from those build days: kids with tape stuck to their sleeves, carefully lining up filter panels; a nurse educator explaining why the fan should be on low to moderate for noise and efficiency; a principal beaming like it’s the best school spirit week he’s ever hosted.

We’ve all learned in recent years that indoor air is not just about comfort; it’s about health. When you breathe in a room with poor ventilation, the particles you exhale hang around for the next person, and the next. Good filtration and better air changes per hour dilute that risk. This isn’t just a pandemic lesson. It’s a common-sense approach to colds, flu, wildfire smoke, dust, and the everyday gunk our lungs quietly deal with. If you’ve ever walked into a classroom after recess and felt the air get heavy before the bell, you know exactly what I mean.

The beauty of these student-built filters is how they bridge the gap between big systems and immediate needs. Many schools do plan to upgrade HVAC systems, and that’s fantastic. But big renovations take time and money, and some buildings have limitations you can’t fix by next Tuesday. A box-fan purifier doesn’t wait on a contract. You can measure a room, calculate a target level of clean air delivery, and build enough units to get there this week. You can position them to avoid drafts, keep them away from little fingers, and still hit impressive reductions in particulate levels. Teachers figure out when to turn them on and how to keep the noise low enough for reading time. Custodians find a rhythm for swapping filters. It becomes part of the fabric of the day, like sharpening pencils or refilling the hand-sanitizer pump.

There’s also the human part of this that gets me every time. Parents talk about fewer absences and fewer frantic last-minute schedule changes. One teacher I met said her classroom “doesn’t smell like a school bus anymore.” Another said she hadn’t had to lose her voice over the winter because she wasn’t shouting over a chorus of coughs. These are small, ordinary victories, the kind that quietly add up to better learning and less stress. When people say clean air is invisible infrastructure, this is what they mean. It’s an environment that helps everyone do a little better without asking for applause.

Of course, the science matters. The filters used in these DIY units are typically MERV-13 or higher, which capture a large share of the tiny aerosols we worry about. The fan’s flow rate and the number of filters set how quickly the air in a room gets pulled through the box. Run the math and you can estimate how many “air changes” you’re getting per hour. Add a CO₂ monitor or a particle counter and you can see, in real time, whether the device is doing what you hoped. In multiple tests, classrooms using these boxes saw significant drops in fine particles—often cutting them by half or more during class—and lab tests with virus surrogates showed removal levels above 99% over an hour under controlled conditions. Again, no single tool eliminates risk. But the combination of dilution, filtration, and common sense steps can make a classroom much safer than it was before.

It’s easy to get cynical about big numbers and big promises. That’s why this story resonates: it didn’t start with a press conference. It started with a kid looking around and asking why the air in her classroom felt tired. It grew into a movement because grown-ups from scientists to legislators said yes to a good idea—and because the idea was simple enough to scale. If you’ve ever felt that public problems are too tangled to touch, this one is proof that some of them aren’t. Sometimes you just need tape, filters, a box fan, and a room full of people willing to try.

There’s a wider lesson here for more than just schools. Workplaces, clinics, community centers, libraries—anywhere people gather indoors—benefit when the air is cleaner. In wildfire season, when smoke slides under doors and turns windows into backlit sepia filters, these boxes have helped families make a haven in their living rooms. In winter, when viruses ride the breath of a crowded bus or cafeteria, they quietly cut the concentration of aerosols. They are not perfect, but they are a practical tool in the toolbox, and they teach us something vital: our built environment is not fixed. We can improve it with both high-tech solutions and smart, low-tech ones.

I think a lot about the photo of Eniola holding her science poster, standing next to a teacher who looks like she could burst with pride. You can see on the table behind them a half-finished box with butterfly stickers and neatly taped seams. It’s the sort of picture you might scroll past on a busy day, but I hope you don’t. I hope you stop and consider what it means that a child helped shape policy, that scientists welcomed a student into real-world testing, and that a state chose to invest in something simple because it worked. That’s an education story. It’s also a public-health story. And more than anything, it’s a reminder that better futures often start as small projects in ordinary rooms.

If you’re wondering what to do with this story, you don’t need to be a policymaker to act. Ask your school what their plan is for indoor air quality. Volunteer on a build day. Donate a box fan, a stack of filters, or even just your time. Encourage science teachers to turn airflow and filtration into a lab where kids can see their own breath on a sensor graph and understand how air moves. The more people who can read a CO₂ number or recognize a MERV rating, the more likely we are to make smarter choices about the spaces where we live, learn, and work.

I don’t know what Eniola will do when she grows up. She’s talked about big goals—public service, leadership, the kind of ambitions adults sometimes dismiss as too grand for a teenager. I hope she keeps them. I also hope the rest of us keep the lesson of her project: when you treat children as partners in solving real problems, they rise to the moment. When you give communities tools they can actually use, they build with both hands. And when you choose cleaner air, you don’t just fight a virus; you invest in clearer minds, steadier attendance, and a calmer kind of everyday life.

So here’s to the little cube in the corner, to the hum you barely hear over the shuffling of notebooks and the ticking of a clock. Here’s to the teacher who plugs it in before the bell, and the custodian who swaps the filters, and the student who once wrote a letter and changed how a whole state thinks about the air its children breathe. We spend so much time looking for big solutions in shiny packages. Sometimes the answer is cardboard, tape, and a belief that even the youngest among us can lead.