The Spiked “Bear Suit” That Fooled the Internet—And the Wild Truth Behind It

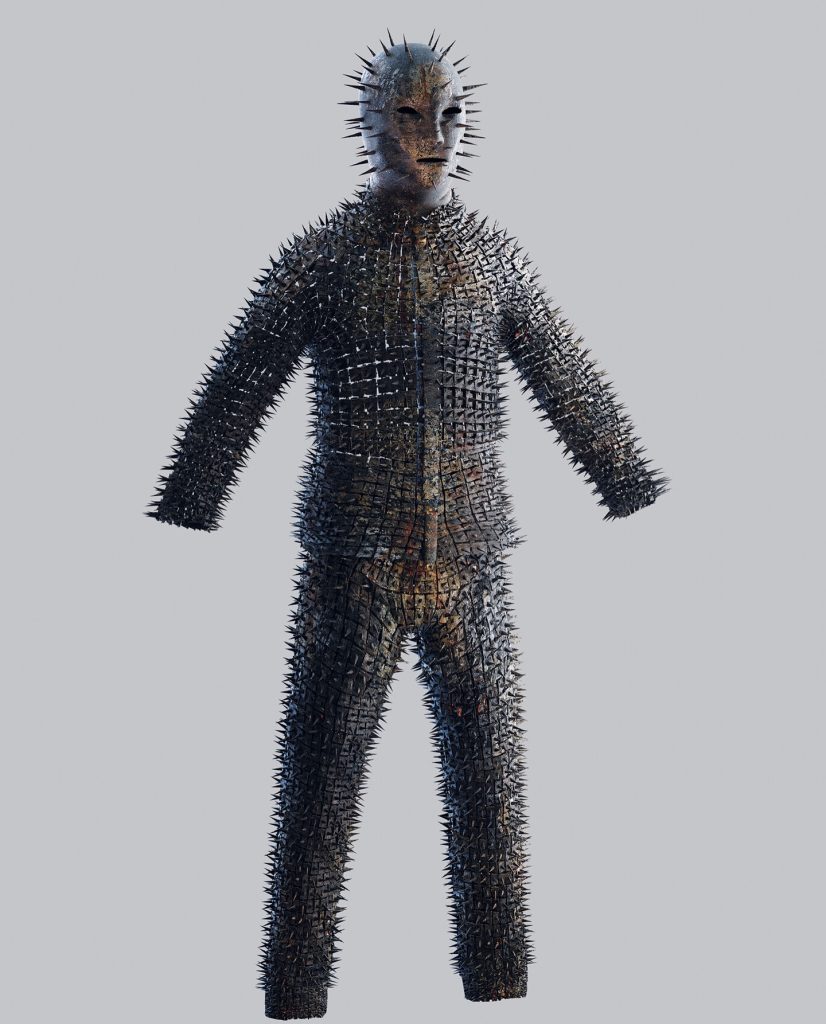

The first time I saw the photo, I almost scrolled past it. A human figure stood in the trees, covered head to toe in short iron spikes, face hidden behind a metal mask that turned the wearer into a bristling silhouette. The caption said it was a Siberian bear‑hunting suit from the 1800s—armor a hunter would put on before facing down a brown bear. It was the kind of internet claim that hits like flint on steel: a single shocking image, a simple story, and our brains do the rest. I stared, pictured snow and breath and claws, and then the questions started. Who made it? Where did it come from? What museum says this is the real thing?

Following those questions doesn’t take you to Siberia. It takes you to Houston, to the Menil Collection—a museum that has spent decades mixing modern art with objects that sit right on the edge of myth. The spiked suit lives there, in a dark, stage‑like room devoted to Surrealist curiosity. The installation is called “A Surrealist Wunderkammer,” and it’s a love letter to the way Surrealist artists collected masks, tools, and artifacts that felt charged with mystery. The suit stands among them like a warning sign made of shadow. Menil curators have even joked about how often it goes viral when the gallery is refreshed. If you ask them whether it really is 19th‑century Siberian bear armor, they’ll give you the careful answer museums are built on: it’s a real object; its exact original purpose is not proven; the internet story is unverified. That’s the honest truth the label can support.

Still, the image is sticky. It fits what many of us want the past to be: brutal, clever, and a little bit unbelievable. On some level it feels plausible because spikes as protection aren’t fantasy. Dog collars in wolf country were studded with metal to stop a throat bite. Soldiers have experimented with studded garments off and on for centuries. And in the late 20th century, an eccentric Canadian inventor named Troy Hurtubise really did build and test a series of “bear suits,” complete with video stunts. So our minds build a bridge: if spiked collars existed, and modern folks have tried impact armor, why not a 19th‑century full‑body suit for bears? The problem is that museums and historians run on paper trails, not vibes. For this suit, the trail doesn’t lead to a Siberian hunting ground with dates, names, and use records. It leads to a Surrealist‑style display designed, in part, to leave room for questions.

When I finally stood in front of a similar Surrealist cabinet years ago—elsewhere, different objects, same approach—I understood why people keep retelling the bear story. These rooms are built to bend your sense of certainty. You see a mask, a drum, a toy, a talisman, a tool, and it’s hard not to write your own caption. The spiked suit invites exactly that kind of storytelling. It’s so aggressively tactile you can feel it in your palms: try to grab this, and you’ll bleed. Try to bite, and you’ll pay. The matching helmet erases the wearer’s face, which is the part that makes the whole thing feel like a creature rather than a costume. Even if you know the provenance is foggy, your imagination charges forward into a snowy forest where someone decided to become a human porcupine to tip the odds.

But there’s a quieter, truer story sitting inside this one, and it’s about how we handle mystery. The Menil didn’t mount that suit in a natural‑history diorama with a rifle propped beside it and a plaque that says “bear armor.” They placed it among wonders, the way Surrealist artists would, and let it hum next to other objects. That decision isn’t a dodge. It’s a way of being honest about what we don’t know. When curators talk about the piece, they don’t swear it was used for hunting. They acknowledge the speculation and keep the door open for better documentation. In a world that loves certainty, this is a more demanding kind of respect—for the object, for the people who once owned it, and for the public trying to understand it.

Pull the camera back, and the folklore around the suit says something about us, too. We share the image because it compresses a survival fantasy into one frame. It promises that danger can be solved with enough hardware and nerve. Spikes are a blunt metaphor for boundaries. We bristle when we’re afraid. We armor up when the world feels close. Sometimes we do it with clothes and tools. Sometimes we do it with stories, posts, and captions. The bear suit story is both—a garment made of metal and a caption made of fear, stitched together so tightly we stop seeing the seam.

It’s also a good reminder of what real survival actually looks like when you take the romance away. People who have lived with bears for generations don’t start by armoring themselves like hedgehogs. They start with dogs, knowledge of wind and terrain, and the kind of patience that hardly ever goes viral. They learn habits for staying out of trouble, because the first rule of living with something stronger than you is not to test the limits. The most important tools are quiet ones: reading tracks, reading seasons, reading your own nerves. In that light, the spiked suit feels less like a field solution and more like a dream of invincibility—one we’ve always been tempted to buy.

None of that drains the object of its power. If anything, it makes it more interesting. There’s a certain category of artifact that matters precisely because it refuses to sit still under a single label. The suit could be armor or costume or satire or ritual or some mixture of all four. It could be a prop, a warning, or a provocation. It might never confess, and that might be the point. The best cabinets of curiosities weren’t libraries of answers. They were rooms where looking became a practice. You step behind the curtain, your eyes adjust, and you remember that not everything that shakes you has a tidy backstory.

There’s also a lesson here for the way we share history online. When a picture arrives with a too‑neat claim, it’s worth pausing long enough to ask who’s saying it and why. If a museum label hedges while a meme shouts, believe the label. If a newsroom checks with curators and reports “unproven,” take that as a sign that grown‑ups have done the homework. It doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the story. It means you hold it the way museums hold fragile things: with care, with context, and with room for new information.

I still think about the suit more than I expected to. Some images are like that—they become shorthand in your head. When I picture it now, I don’t see a hunter charging a bear. I see a person at the threshold of fear, building an exoskeleton to make the fear obey. It’s strange and moving that an object can do that to a viewer a century later. Maybe that’s the most honest way to honor it: not by insisting it was used exactly as the internet says, but by admitting that it still works on us. It makes us feel the old pull between risk and safety, wildness and control, myth and proof.

So the next time the spiked suit pops up in your feed, you’ll know the two truths that can live together. The first is that the legend—“hunters wore this to fight bears”—is a great story with no solid documentation behind it. The second is that the suit is real, standing quietly in a Houston gallery built to celebrate wonder, and its power doesn’t depend on an unbroken chain of paperwork. We can appreciate the mystery without flattening it into a claim it can’t carry. We can let it be what it is: a human outline bristling with questions, a reminder that curiosity can be sharper than fear, and a nudge to check the label before we share the caption.