Los Angeles Replaced About 160,000 Streetlights with LEDs by 2019—Slashing Power Use ~64% and Rewriting What the City Looks Like After Dark

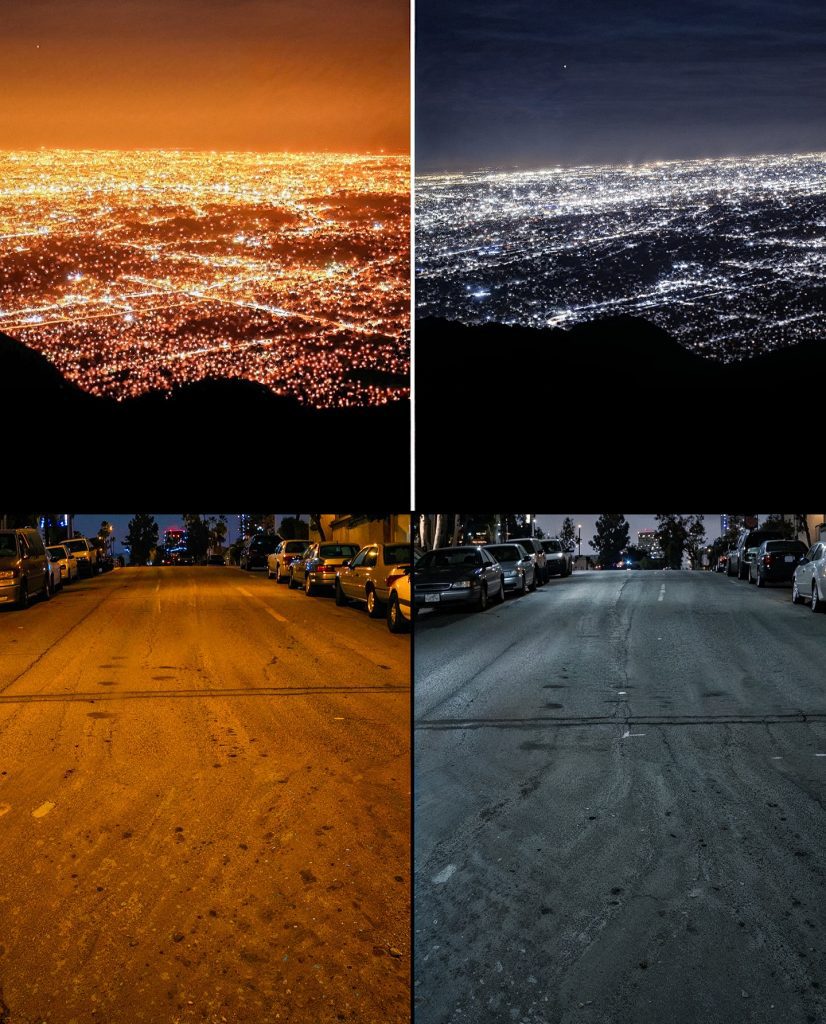

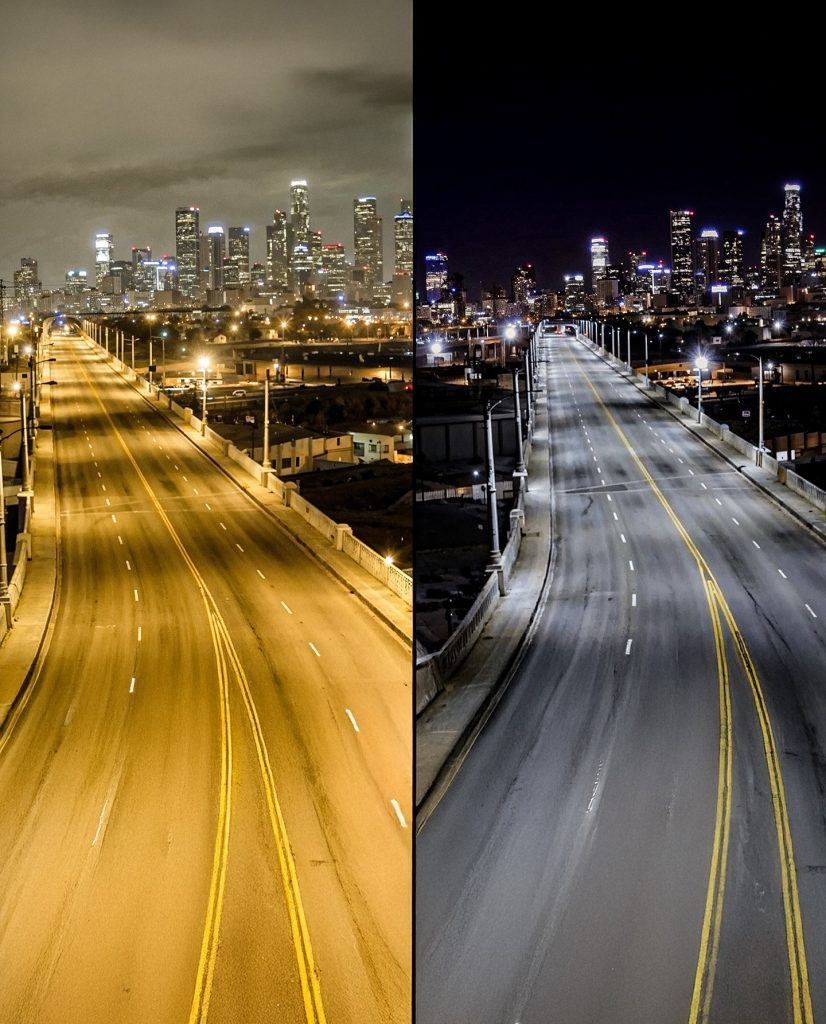

I still remember the first late-night drive I took after Los Angeles finished most of its streetlight makeover. The sky over the basin didn’t look like a campfire anymore. For decades, the old high-pressure sodium lamps had painted the city in a syrupy orange haze you could spot from a plane window or a hiking trail above Griffith Park. That amber wash felt iconic—comforting even—but it was also a kind of mask, bright in all the wrong directions and hungry for power. By 2019, L.A. had converted roughly 160,000 streetlights to LEDs, and the city at night looked different: sharper along the curb line, cooler at intersections, and, in many places, simply clearer.

The numbers behind the change are as striking as the photographs. Swapping sodium for LED cut streetlight electricity use by around sixty-four percent—about 114 gigawatt-hours each year. If you like comparisons, that’s enough energy to run well over ten thousand typical homes for a year. It also means fewer truck rolls for bulb changes, because LEDs last longer, and more precise control of light levels thanks to small networked nodes that can ping the city when a fixture fails. A streetlight used to be a one-way device: throw photons and hope for the best. Now it’s more like infrastructure with a dashboard.

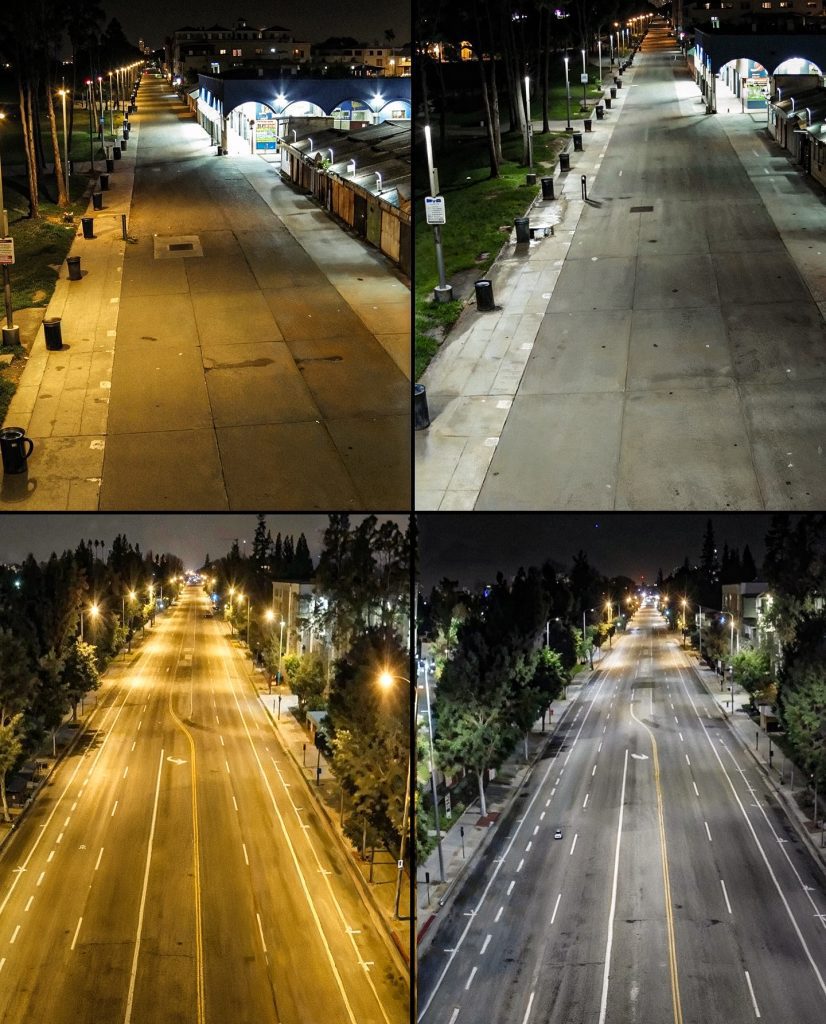

But the part you feel, the human part, reveals itself when you’re walking a block you know well. Under LEDs, sidewalks read as sidewalks. You can tell gray from brown, navy from black, without guessing. The old sodium lamps made everything a shade of pumpkin; they were bright, but they flattened the world. It’s no small thing to see the city’s actual colors at night—the mural on the corner, the green of a parkway tree, the difference between a puddle and a patch of asphalt. Drivers notice it at crosswalks. Cyclists notice it in the way reflective tape suddenly pops. Even window glass looks different—less halo, more edge.

Of course, changing the way a whole city glows after dark isn’t as simple as screwing in a new bulb. In the beginning, some blocks felt almost too bright, a cold wash that was a little hard on the eyes. Residents wrote to the city. Engineers listened. The next iterations leaned warmer and added better optics and shielding, pushing more light down onto the pavement and less into bedroom windows or the sky. The goal wasn’t to make midnight feel like noon. It was to put light where people actually needed it and stop wasting it in places where no one did.

That last part is crucial. The orange dome you used to see hovering above Los Angeles wasn’t only a color—it was waste made visible. Sodium lamps threw a lot of their glow sideways and upward, where it served no purpose. Unlike those, modern LED fixtures can be shaped. Think of them as little stage lights with lenses, focusing brightness on the lane line, the crosswalk bar, the sidewalk edge. When you do that tens of thousands of times, you begin to shrink the dome. On clear nights after the conversion, lookouts that once stared into a murky orange soup suddenly saw a patchwork of white lines tracing major streets. It wasn’t “dark,” exactly, but it was less fogged.

There was another surprise: how different the skyline photographs looked. The classic postcard shot of the basin used to glow like a hearth—romantic, sure, but unrealistic. The updated images have more contrast. Buildings stand apart from the background. Freeways slice in cool ribbons. Bridges pick up a soft clarity along their railings that you can actually follow with your eyes. The same camera settings that once made the city look molten now reveal a grid. It takes some getting used to, but it matches how it feels to walk around.

Savings are the quiet backbone of the story. Streetlights are some of the most ordinary things a city owns, but there are a lot of them, and they burn for many hours every day of the year. Cut the power bill by nearly two-thirds and you free up money for things that residents see and feel: repaving a block, adding a crosswalk, keeping library hours longer. Lower maintenance helps, too. LEDs don’t fail like old bulbs—they fade so slowly that crews can schedule replacements instead of racing from one outage to the next. And because the fixtures “talk,” the city doesn’t have to wait for a phone call to know a light is out on a specific pole.

Safety often comes up in conversations about lighting, and here, nuance matters. Brighter isn’t always safer; smarter usually is. The most useful light is placed thoughtfully—downward, even, and at a level that lifts visibility without washing out your pupils. That’s what many of the new fixtures achieve. You can read faces at a bus stop. You can see a dog on a leash at the end of the block. Drivers can spot a pedestrian stepping off the curb a beat earlier. If you’re walking home, that extra beat can feel like confidence. If you’re driving, it feels like time to do the right thing.

Then there’s the simple comfort of reliability. In the sodium era, it wasn’t unusual to see a whole run of lights dark because they shared a failing circuit. Now, issues get flagged within the system. That’s not magic; it’s just what happens when you treat a city’s lights like a network instead of thousands of separate flashlights. The city can dim late at night on quieter streets and bring levels up during an emergency or an event. That kind of responsiveness sounds technical, but it lands as care: someone is paying attention.

Did everyone love the change? Not at first. The orange glow had nostalgia on its side, and nights did feel “colder” in the opening months. People complained about glare outside bedroom windows or a fixture that felt mis-aimed. The process of adjustment made the program better. Warmer color temperatures, careful aiming, and shielded optics became the rule, not the exception. The truth is, you don’t know how a light will feel until you’re standing under it at midnight. The Bureau of Street Lighting took those notes and tuned things block by block. That’s the hidden advantage of LEDs: not only do they save energy; they’re adjustable in a way old lamps never were.

There’s also an environmental thread that’s easy to miss. Mining less electricity from the grid means fewer associated emissions. You may never read the back-of-the-envelope math, but you feel the outcome in cleaner air and a grid with a little more breathing room on hot nights when everyone’s air conditioner kicks on. The sky itself benefits. Blue-heavy light scatters more in the atmosphere, but well-designed fixtures that point downward and use warmer color temperatures help reduce that scatter. The result isn’t a pristine, star-studded dome—this is still Los Angeles—but it’s a step away from the perpetual twilight that orange lamps created.

Walk any neighborhood and the differences stack up in smaller ways. The corner store’s painted sign looks like it does in the daytime. The bus shelter ad is legible without shouting. Street trees throw softer shadows that don’t hide what you need to see. The glow against building facades is gentler, less like a blaze and more like a guidance cue. Every improvement is modest on its own; together they reshape how safe, usable, and welcoming a block feels after dark.

The best proof might be how quickly the new look became normal. Ask people who moved to Los Angeles after 2019 what the city’s night used to be, and many won’t know the answer. They’ve never lived under the orange. Their mental picture of L.A. after sunset is the cleaner grid, the whiter corridors along major streets, the tighter pools of light on neighborhood corners. And to the longtime residents who still miss the nostalgia, it’s worth remembering that iconic doesn’t always equal ideal. The orange was a mood. The LED era is a tool.

What sticks with me is how the change reframed the city’s relationship with light itself. Instead of treating illumination like a blanket to toss over everything, Los Angeles began to place it deliberately—on the crosswalk bar where wheels meet paint, on the sidewalk where steps meet cracks, on the sign where letters meet eyes. That’s the quiet revolution behind the statistics. Less waste. More intention. A city that looks and feels like someone arranged it on purpose.

It’s easy to talk about LEDs as technology, but the better word might be attention. Attention to the bill you pay, to the bedroom window you don’t want flooded, to the stretch of curb where a mother pushes a stroller home from the bus. Attention to how people actually move through a place after dark. That’s what the swap bought Los Angeles: the power to focus. The night didn’t get brighter everywhere; it got smarter where it counts. And the skyline, once baked in orange, now looks more like a promise than a bonfire—proof that a million small decisions can add up to a city you can see more clearly.