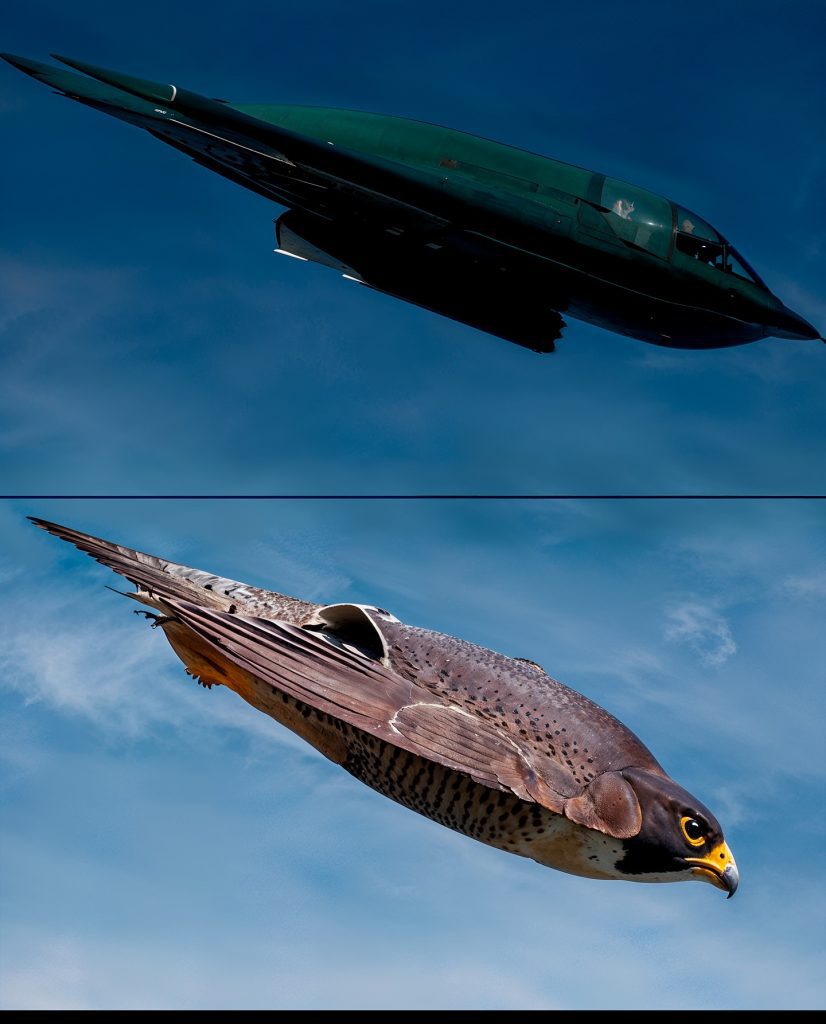

From Jet Planes That Imitate Falcons to Cars Modeled After Fish — The Photos That Prove Nature Is the Greatest Designer of All Time

Long before humans learned to draw, sketch, or code blueprints, nature had already mastered the art of design. Every curve of a leaf, every feather on a bird, every scale on a fish is the result of millions of years of evolution — a perfect, silent engineering process that continuously refines what works and discards what doesn’t. The most brilliant minds in modern design and engineering, from architects to scientists, have always known this truth: if you want to invent something revolutionary, look to the world that has been solving complex problems for billions of years.

The term for this quiet partnership is biomimicry — the practice of studying natural forms, patterns, and systems to inspire human innovation. But the truth is even simpler. We copy nature because it works. Whether it’s the stealth of a falcon or the structure of a seashell, the best solutions we’ve ever engineered often turn out to be rediscoveries of what life has already perfected.

Consider the peregrine falcon — the fastest animal on Earth. When it dives through the sky, it reaches speeds of over 200 miles per hour, its sleek, teardrop-shaped body cutting through the air with astonishing efficiency. Engineers studying the bird’s anatomy realized that its curved wings and streamlined silhouette minimize drag in a way that even modern aerodynamics struggled to replicate. When they designed the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, one of the most advanced aircraft ever built, they unknowingly followed the same blueprint. Both the falcon and the bomber share similar contours — wide, tapering wings and smooth, unbroken lines that slice through air resistance. Nature, it seems, had already solved the problem of flight long before humans did.

And it’s not just in the skies that nature’s blueprints show up. The ocean, a vast laboratory of fluid dynamics, has inspired some of the most significant technological breakthroughs of the modern era. The boxfish, for instance — a small, oddly cube-shaped marine creature — became the unlikely muse for Mercedes-Benz engineers when they designed a concept car that needed to be both aerodynamic and structurally stable. Despite its boxy shape, the fish glides through water with minimal drag thanks to the subtle curvature of its body. The resulting Mercedes-Benz Bionic Car mirrored that design, boasting an incredible drag coefficient of just 0.19 — one of the lowest ever recorded for a vehicle. Nature’s compact swimmer had quietly guided the creation of one of the most efficient cars on land.

Even something as delicate as a butterfly’s wing has inspired entire industries. The brilliant blue of a morpho butterfly, for example, doesn’t come from pigment but from microscopic structures that reflect light in specific ways — a phenomenon known as structural coloration. Engineers have used this principle to develop more vibrant, fade-resistant paints, anti-counterfeit materials on banknotes, and even energy-efficient display screens. Once again, nature’s intricate beauty turned out to be science in disguise.

For astronauts and scientists, inspiration has come from creatures that seem ordinary but are anything but. Take the humble gecko — small, silent, and capable of walking upside down on glass. Its feet are covered with millions of microscopic hair-like structures called setae, which use van der Waals forces to cling to surfaces without any adhesive. NASA engineers, inspired by this phenomenon, developed gecko-inspired gripping pads that can hold tight in microgravity — allowing astronauts to manipulate objects in space where glue and suction don’t work. It’s an elegant reminder that the smallest creatures often hold the biggest secrets.

Meanwhile, in the world of robotics, researchers have turned to cheetahs, octopuses, and dragonflies for answers. Boston Dynamics, for instance, modeled its “Cheetah” robot after the animal’s flexible spine and limb coordination, enabling it to run at speeds once thought impossible for a machine. In underwater robotics, scientists have designed soft-bodied robots that mimic the movements of octopuses, capable of squeezing through tight spaces and adapting to unpredictable environments — a potential game-changer for underwater exploration and rescue missions.

Even the simple act of gliding through air — something humans have dreamed of since the beginning of time — owes much to nature’s example. The wingsuit, now a staple of extreme sports, takes direct inspiration from the flying squirrel. With stretched flaps of skin connecting its limbs, the squirrel can glide from tree to tree with remarkable control, covering vast distances without ever flapping a wing. Engineers studying this mechanism discovered that a similar design could allow humans to glide with a ratio of about three meters forward for every meter dropped — an astonishing level of efficiency for something purely driven by air resistance and body shape.

In architecture, too, nature has quietly shaped our skylines. The Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe, is one of the most remarkable examples. Its design was modeled after termite mounds, which maintain near-constant internal temperatures despite extreme outside heat. The building uses a natural ventilation system inspired by these mounds, reducing energy use by up to 90%. It’s a testament to the idea that sustainability isn’t a new human concept — it’s been the cornerstone of natural design all along.

Then there’s the kingfisher, a bird whose sharp beak inspired the design of Japan’s famous bullet train. When engineers were struggling with noise issues caused by trains entering tunnels at high speed, they turned to the bird for answers. The kingfisher dives from air to water without making a splash, its beak shaped to minimize shockwaves. By modeling the train’s nose after it, engineers reduced noise, increased speed, and improved energy efficiency. It’s a perfect example of how beauty and function coexist seamlessly in nature.

Some of the most surprising designs come not from animals but from plants. The lotus leaf, for instance, has inspired an entire class of self-cleaning materials. Its surface is covered in microscopic bumps that cause water droplets to roll off, carrying dirt with them. This “lotus effect” is now used in waterproof coatings, solar panels, and even textiles. Similarly, the shape of shark skin, covered in tiny ribbed scales called dermal denticles, inspired swimsuits that reduce drag and even antimicrobial surfaces that resist bacterial growth. Every texture, every surface pattern in nature exists for a reason — often one that humans only realize centuries later.

What makes all this so extraordinary is that these designs aren’t products of random chance. Evolution is the ultimate testing ground, one that rewards efficiency, adaptability, and resilience. The falcon’s wings, the shark’s scales, the lotus leaf’s surface — they are the results of millions of years of refinement. When humans borrow from them, we’re tapping into that same history of trial and error, standing on the shoulders of a designer infinitely more experienced than any of us.

It’s no wonder that nature continues to inspire the future of technology. In a world increasingly focused on sustainability and efficiency, the answers often lie not in creating something new but in rediscovering what already works. Researchers are now studying whale fins for wind turbine blade designs, spider silk for lightweight materials stronger than steel, and coral reefs for architectural models that can withstand rising sea levels. Even artificial intelligence is beginning to emulate biological processes, using neural networks modeled after the human brain to solve problems in ways that mimic thought itself.

When you look at a falcon in flight or a leaf repelling water, it’s impossible not to be humbled. Nature doesn’t waste. It doesn’t overcomplicate. Every line, every motion, every color has purpose. In contrast, much of human design is still about catching up — trying to match the effortless harmony that the natural world achieves without blueprints or budgets.

As photographers capture side-by-side images of birds and aircraft, fish and cars, leaves and skyscrapers, what we see is not coincidence but a reflection of a timeless truth: nature is the original engineer, and we are its students. We’ve built our rockets to soar like hawks, our submarines to swim like whales, and our cities to breathe like forests. In every invention we claim as ours, there’s a whisper of the natural world reminding us — “I thought of it first.”

Ultimately, it’s not about imitation but respect. To design like nature is to think like nature — to value balance, function, and sustainability over excess. Every breakthrough inspired by biology is a small step toward harmony, a reminder that we are not separate from this planet’s design but part of it.

So the next time a jet streaks across the sky or a sleek car glides down the road, remember the falcon and the fish that made it possible. Remember that in every piece of technology, there’s a trace of wild genius — an echo of evolution’s hand. Because when it comes to design, no human mind has ever come close to the brilliance of the one that shaped the wings of a bird, the shell of a turtle, or the curve of a wave. Nature doesn’t just inspire — it defines perfection.