Photographer Captures the Breathtaking Symmetry of Iranian Architecture — Where Math, Faith, and Light Become One

There’s a kind of silence inside Iran’s mosques that doesn’t just come from the walls — it comes from the centuries that built them. Every corner, every arch, and every tile seems to breathe with history. When you step inside, you don’t just see architecture — you feel precision and poetry working together. And that’s exactly what photographer Ghasem Baneshi has managed to capture through his lens.

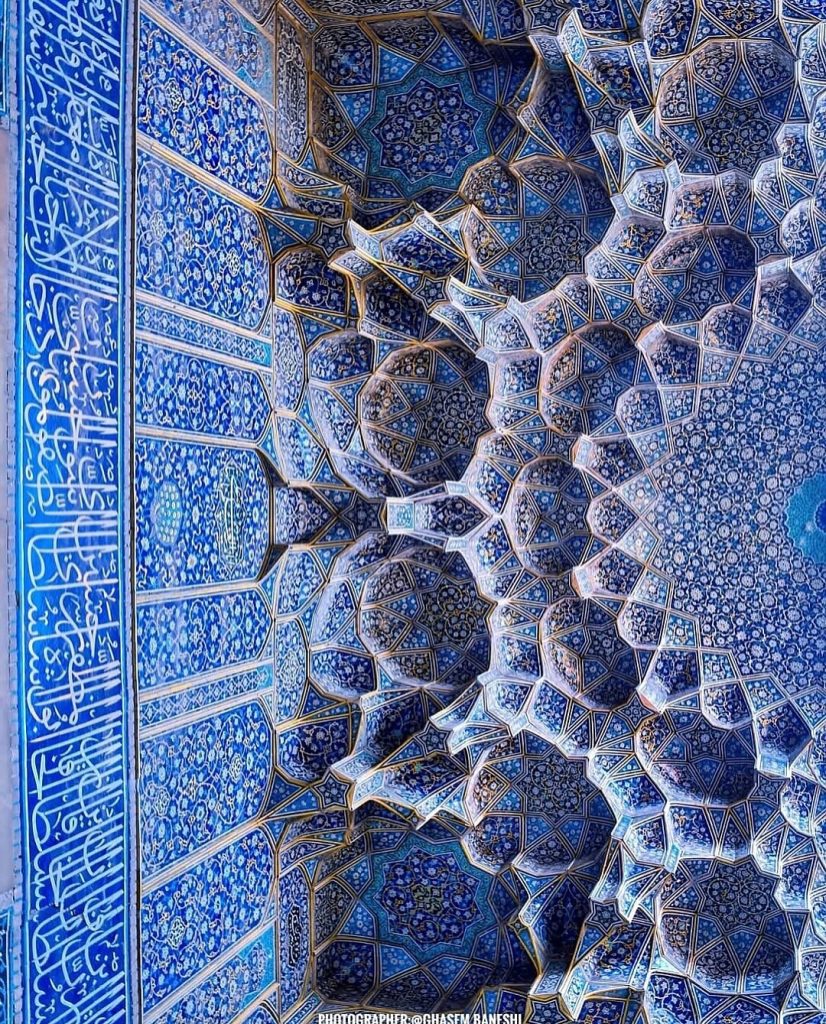

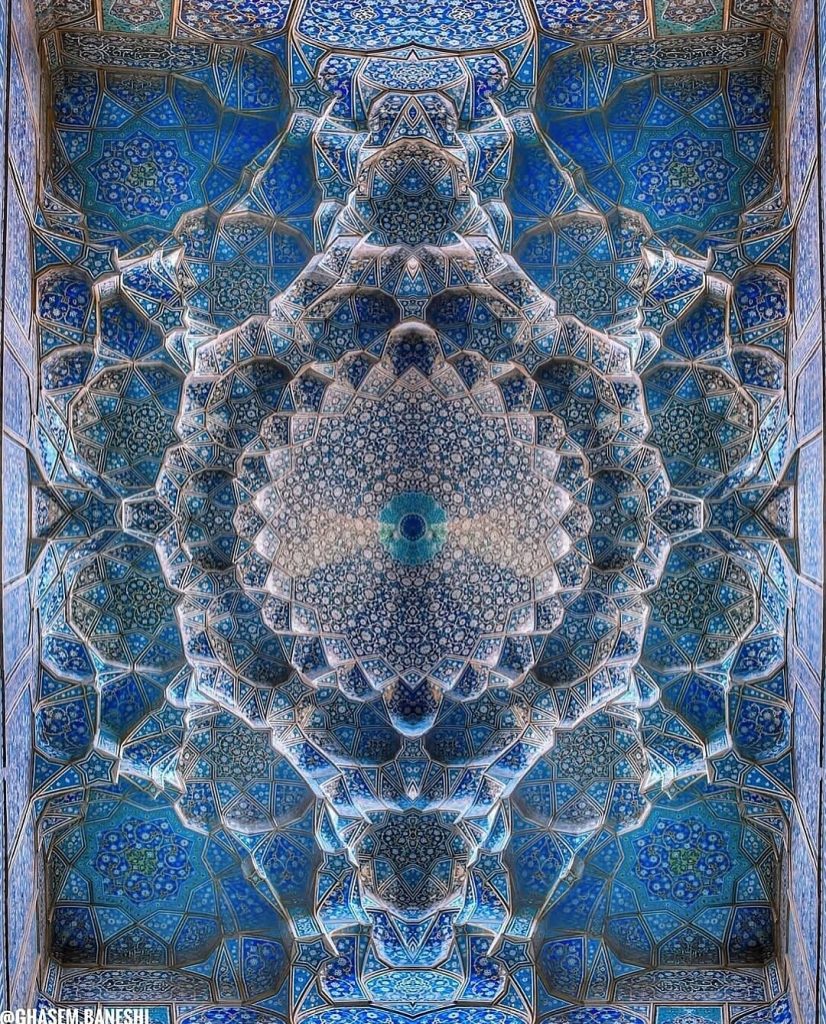

In a world where modern architecture often screams for attention, Baneshi’s work whispers. His photographs of Iran’s “muqarnas” ceilings — the intricate, honeycomb-like domes found in mosques across Isfahan, Shiraz, and Yazd — remind the world that true art doesn’t need to shout. It’s already eternal.

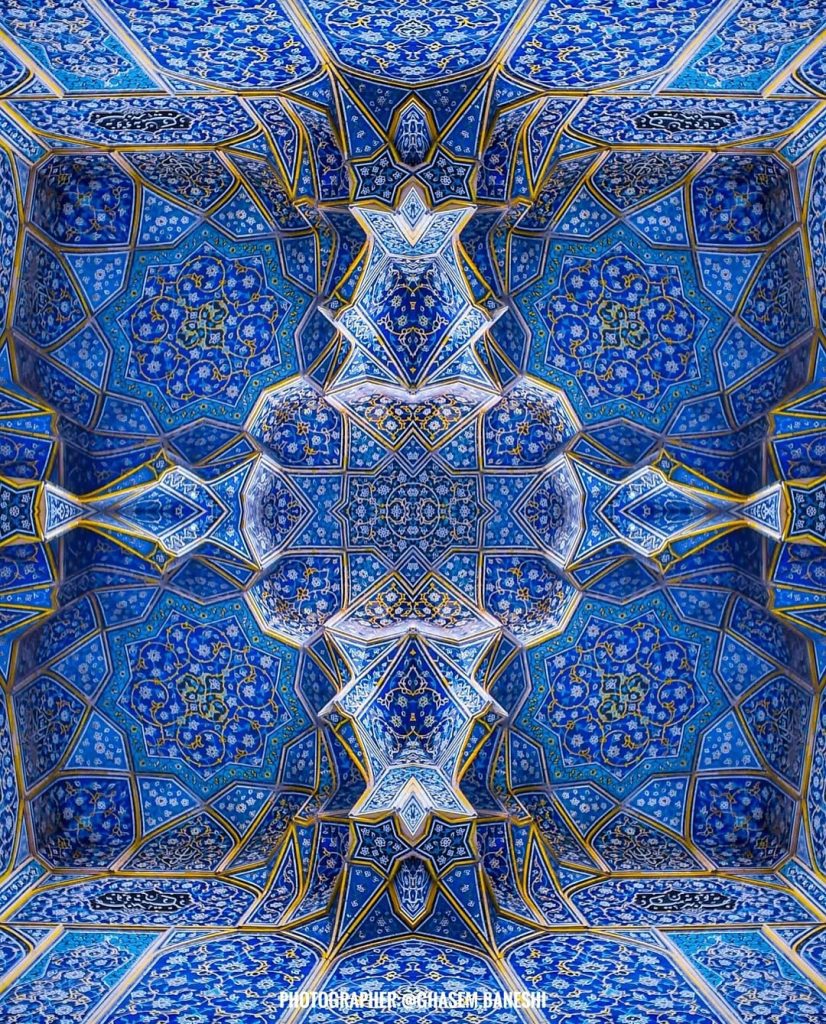

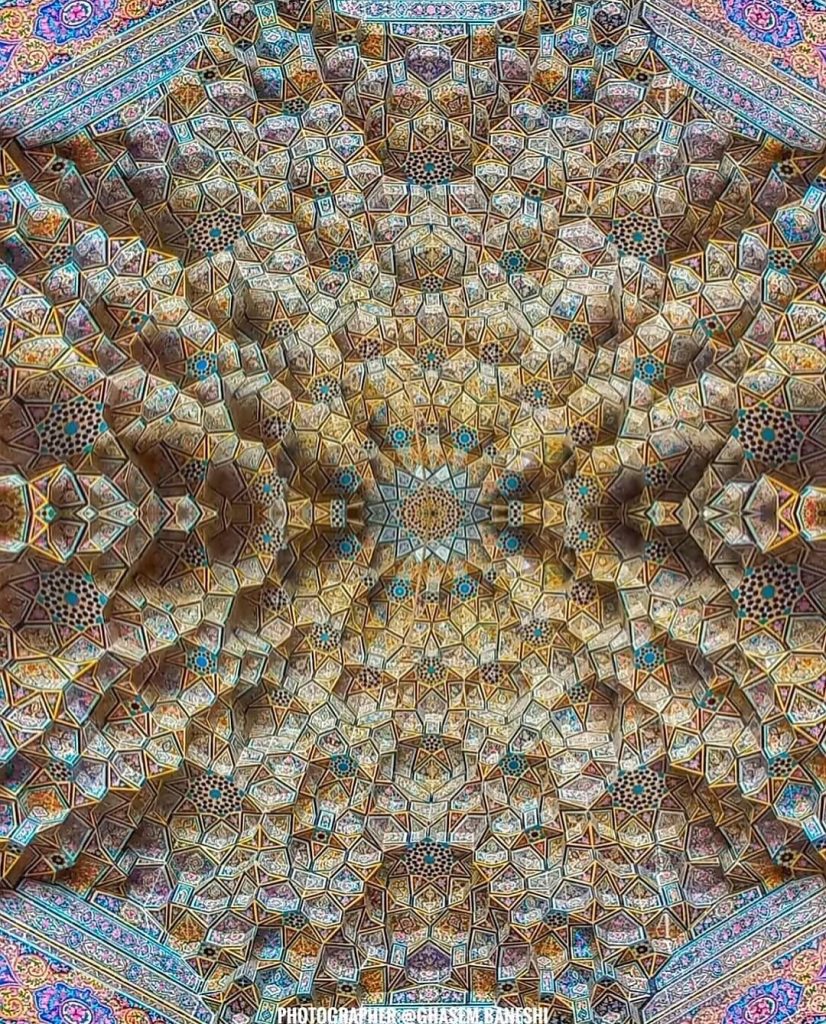

The photos are mesmerizing: infinite shades of blue and turquoise arranged in patterns so mathematically perfect, they feel otherworldly. Each ceiling looks like it was built by both a mathematician and a poet — someone who understood geometry as a spiritual language. These designs, called muqarnas, date back to the 11th century and have been refined over generations of Persian craftsmen. The shapes form a cascade of miniature domes, arches, and niches that seem to pull light down from the heavens.

In Baneshi’s images, sunlight filters through colored glass windows, bouncing softly off thousands of glazed tiles. The result is a kaleidoscope of color that feels alive — a living geometry that shifts as the day moves. There’s an almost divine balance to it, as if these ceilings were built not just for prayer, but to make people look up in awe.

Isfahan, often called “half the world” in Persian poetry, is where many of these architectural wonders stand. The city’s Naghsh-e Jahan Square, a UNESCO World Heritage site, holds some of Iran’s most remarkable examples of Safavid architecture — from the Shah Mosque to the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque. These places have survived wars, invasions, and time itself. And yet, when you look at them through Baneshi’s photos, they appear untouched by any of it — as if frozen in a moment of divine perfection.

What makes these photographs even more remarkable is how they reintroduce the world to the genius of Persian design. In the West, the word “Islamic architecture” often evokes the great mosques of Istanbul or the palaces of Andalusia, but Iran’s influence runs deeper. It was Persian architects and craftsmen who perfected many of the design principles that later spread across the Islamic world — the pointed arch, the dome’s double-shell structure, the concept of symmetry as a reflection of divine order.

Iran currently counts 29 UNESCO World Heritage sites, and many of them owe their recognition to this legacy. From the poetic gardens of Shiraz to the desert city of Yazd, Persian architecture is built around balance — between shadow and light, silence and sound, earth and sky.

Baneshi’s photos have gained thousands of admirers on social media, but they do more than just impress. They reconnect people to a forgotten relationship between beauty and thought. Each image invites the viewer to pause and wonder — not only at the technical brilliance behind those patterns, but also at the philosophy that inspired them.

In Islamic art, geometry is not decoration — it’s devotion. The endless repetition of patterns reflects the infinite nature of God, and the symmetry reminds worshippers of unity and order in creation. The tiles, the arches, the domes — they all tell the same story: that perfection is found not in luxury, but in harmony.

For centuries, artisans worked without machines or blueprints. Each tile was hand-cut, each color mixed with natural pigments. Many patterns were drawn using nothing but a compass and a ruler. Yet, when you look at them, they feel so complex that even modern software would struggle to replicate them. The craftsmen didn’t just build mosques; they built experiences — spaces where faith met logic, and prayer met design.

In a time when many people only see Iran through political headlines, Baneshi’s work feels like a much-needed reminder of what lies beyond that narrative. It’s a country where art has always been more than beauty — it’s a way of thinking. The Persian word for “architecture,” me’mari, comes from “imarat,” which means “to build,” but also “to give life.” To the Persian mind, creating something beautiful was a form of worship.

That’s why even centuries later, these buildings still move people. You don’t have to be religious to be touched by their serenity. You don’t even have to understand the language or the culture. The symmetry speaks for itself. It’s universal.

Many of Baneshi’s photos come from Isfahan’s Shah Mosque, where the tiles shimmer like the ocean, and from the Jameh Mosque of Yazd, whose dome looks like it’s made of woven light. He often captures the ceilings from directly beneath them, creating the illusion of infinite space. Some viewers say his work makes them feel dizzy, others say it makes them feel calm. But no one can deny that it stirs something deep — something we’ve all forgotten how to feel in our rushed, digital world.

There’s a sense of patience in these buildings that modern life has lost. Every tile placed, every curve drawn, was a quiet act of focus. Standing under those domes, or even looking at them in Baneshi’s photos, you feel small — but in a comforting way. You realize how tiny human effort is compared to the eternity of beauty.

It’s fitting that Iran’s architecture has endured through centuries of change. Empires have fallen, cities have evolved, but these patterns — these precise, fragile, perfect patterns — remain. They were made to last not because they’re strong, but because they’re meaningful.

Maybe that’s why Baneshi’s photos resonate so much today. In a world obsessed with the new, his work reminds us of the eternal. In a time when we scroll endlessly, his images make us stop. Look up. Breathe. Feel awe.

The blue ceilings of Iran are not just designs; they are the echoes of a civilization that understood something simple yet profound: that art can be a prayer, and that true beauty doesn’t fade — it only waits to be rediscovered.