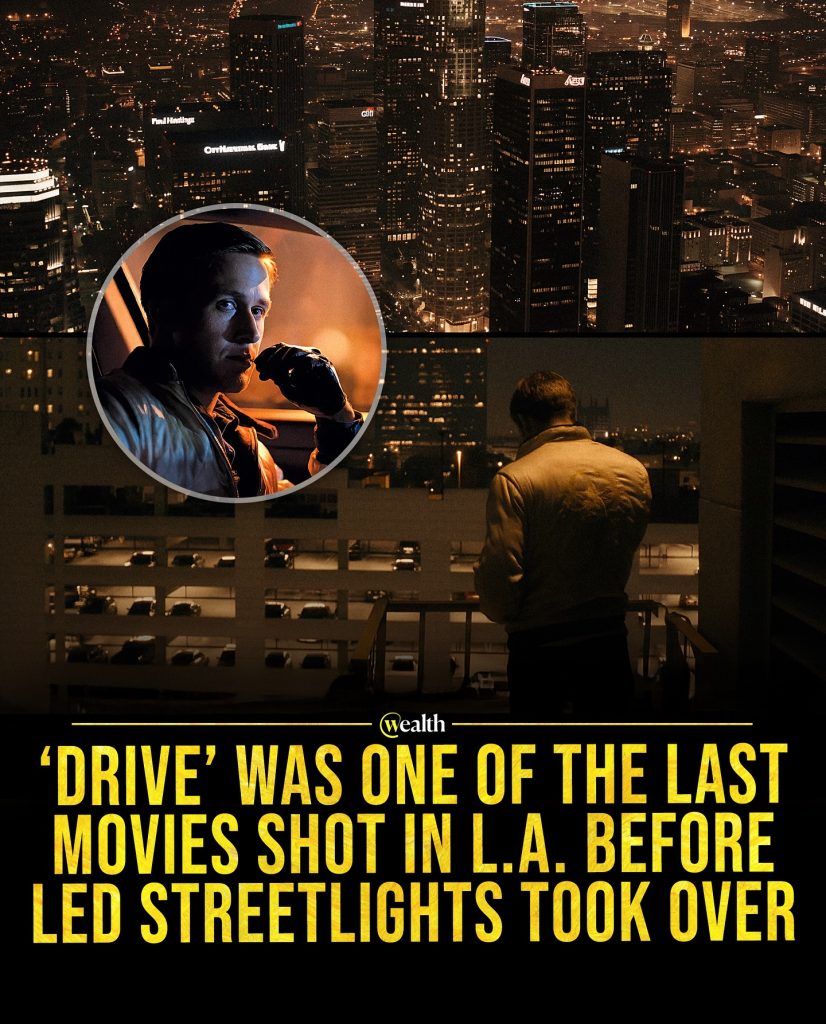

Before LEDs changed Los Angeles forever, Drive captured the city’s final amber nights — the haunting beauty of L.A. under its last sodium streetlights

There’s a quiet sadness hidden in the glow of Drive. If you’ve ever rewatched Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2011 masterpiece, you know the look — that warm, amber light that wraps Los Angeles like a dream. The way the skyline hums with gold and copper, the soft haze that hangs over the freeway at night, the way Ryan Gosling’s nameless driver seems to move through a city bathed in eternal twilight. What you’re seeing there isn’t just cinematic style — it’s history.

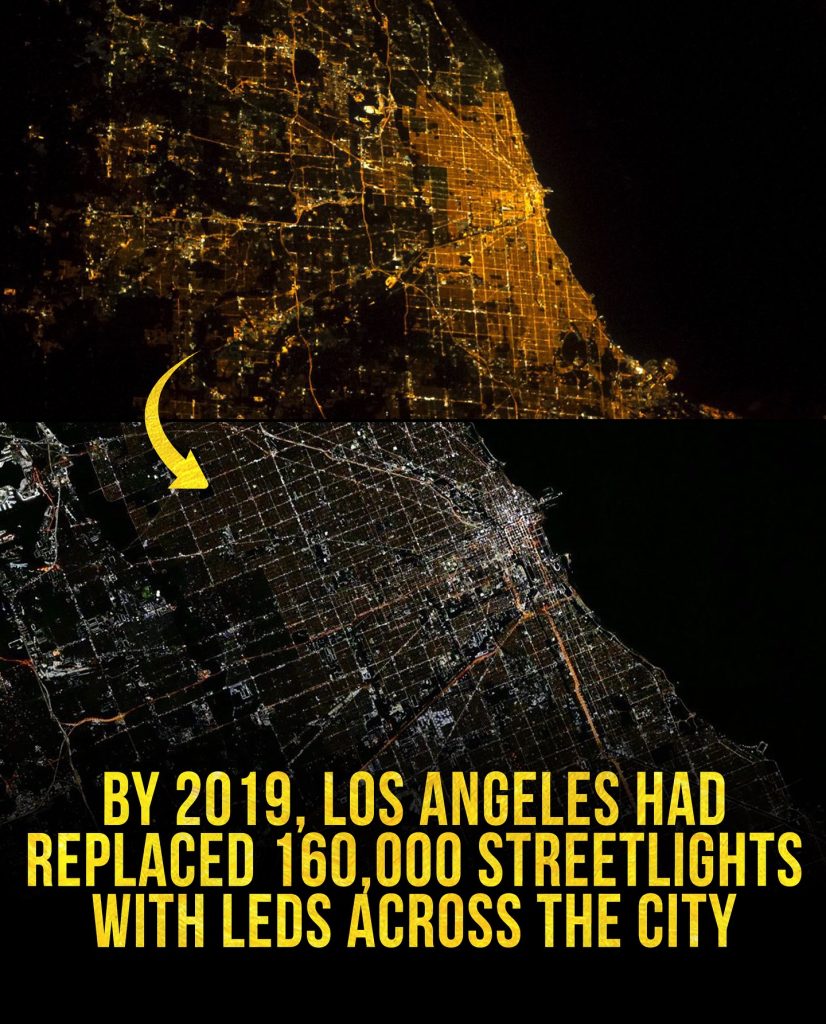

When Drive was filmed, Los Angeles was on the verge of a massive transformation. The city’s iconic orange glow — produced by high-pressure sodium-vapor streetlights — was about to vanish. In the years following the film’s release, Los Angeles converted nearly 160,000 streetlights to bright white LEDs. By the early 2020s, about 98% of the city’s lights had been replaced, ending decades of that signature warmth that had defined its nights.

To understand what makes Drive so visually unique, you have to appreciate what those old sodium lights meant to the city. For generations, they shaped how people experienced Los Angeles after dark. That orange tint wasn’t just light — it was atmosphere. It softened the hard edges of buildings and bathed the streets in a glow that made everything feel cinematic. For directors and cinematographers, it was a built-in filter, a visual texture that told stories of romance, loneliness, and danger all at once.

Drive took that glow and turned it into emotion. Every frame in the movie breathes with the city’s pulse — from the glittering skyline of downtown to the empty parking lots where Gosling’s character waits in silence. Cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel shot the film with deep respect for the way light interacted with the urban landscape. The amber haze wasn’t just beautiful — it was honest. It was how Los Angeles really looked back then, before the switch flipped and the nights turned cold and white.

When you watch Drive now, it feels like watching the end of an era. The film’s story — about isolation, quiet love, and sudden violence — mirrors the mood of a city losing its old soul. The driver moves through a Los Angeles that’s alive but fragile, as if he knows he’s driving through something that won’t last. That orange light that falls across his car windows, that hue that turns the skyline to honey, it’s the color of memory — of something fading right in front of you.

There’s a reason that so many fans and photographers still chase that “Drive look.” It’s not just about the lighting or the color grading — it’s about the feeling. The way those old streetlights made you see the city differently. Under their glow, Los Angeles didn’t just look alive — it looked mysterious, endless, cinematic. The change to LEDs brought clarity and efficiency, but something intangible was lost along the way.

City officials had good reasons for the switch, of course. The move to LED lighting was part of a global sustainability effort. The new lights were brighter, used less energy, and saved millions in power costs. From an environmental and economic perspective, it was the right call. But in terms of atmosphere — that invisible emotional texture of a place — it marked a turning point. The city that once glowed with golden fog now shimmered in sharp white light. The dreamy warmth of nighttime L.A. gave way to something cleaner, colder, and flatter.

It’s strange how progress can sometimes erase the poetry of everyday life. Those orange streetlights weren’t perfect — they distorted colors and cast everything in a monochrome hue — but they made the city feel human. Artists, filmmakers, and photographers loved them because they didn’t just illuminate; they transformed. They turned gas stations into stages and back alleys into film scenes. You could stand anywhere under that glow and feel like you were inside a story.

Drive was one of the last films to capture that glow in its purest form. After 2011, the change happened quickly. One by one, the amber lights were replaced. Downtown, the switch came early. Hollywood Boulevard soon followed. Even the neighborhoods tucked deep into the Valley began to change. The difference was immediate — the city’s nights became clearer, but somehow emptier. The skyline lost that golden warmth that once defined it in postcards, photographs, and movies.

Rewatching Drive today feels like looking at a time capsule. You can almost sense that it’s the last breath of something — the final document of a Los Angeles that glowed like a candle instead of a computer screen. When Gosling’s character stares out at the city from his apartment window, he’s not just looking at the lights — he’s looking at the end of the old L.A.

The irony is that Drive wasn’t trying to be nostalgic when it was made. It was a film of its time, not a love letter to the past. Yet in retrospect, it became exactly that — unintentionally capturing the final moments of a city’s visual identity. Today, filmmakers have to recreate that look artificially with filters and digital color correction. But Drive had it naturally, because that’s how Los Angeles really looked.

Even for locals, the memory of those nights lingers. Ask anyone who grew up in the city before the LEDs — they’ll tell you about the orange haze that floated above the skyline, the way it glowed after rain, the feeling of driving down empty freeways at midnight with that warm light stretching ahead like an open invitation. That world doesn’t exist anymore, except in memories and movies like Drive.

Maybe that’s why the film continues to resonate, more than a decade later. It’s not just the music, or the romance, or the tension — it’s the light. It’s the way it makes you feel something that’s gone. Watching Drive now is like remembering a version of Los Angeles that felt softer, slower, more mysterious. It’s not just nostalgia; it’s preservation.

Art has a way of catching what time erases. Drive didn’t mean to save the orange nights of L.A., but it did. Every time you play it, you’re seeing a city that no longer exists — one that glowed under sodium skies, where every shadow had warmth and every night felt infinite. The film didn’t just tell a story about a man — it told one about a city in transition, caught between the romantic past and the clinical future.

And maybe that’s what makes Drive so hauntingly beautiful. It’s not just about what happens — it’s about what’s lost in the background. A film made on the edge of change, holding onto the last flicker of something golden before the lights went out.

Los Angeles still shines, of course — just differently now. The skyline is whiter, cleaner, sharper. The city looks more efficient, more digital. But somewhere inside that brightness, a part of us still misses the orange nights — the ones Drive kept alive forever.