The Most Expensive Things That Are Still Lost on the Titanic

MARGARET “MOLLY” BROWN’S DIAMOND NECKLACE — $600,000

The Unsinkable Molly Brown left Cherbourg wearing only modest jewelry, but she packed her most spectacular diamond-and-sapphire necklace in a small leather case stored in her first-class stateroom. After the collision she escaped in Lifeboat 6, immediately working an oar and later raising money for third-class survivors. In the chaos her jewel case never made it topside. Brown’s 1913 insurance claim lists the piece at $20,000; adjusted for inflation, the pendant now sits near $600,000. Somewhere along a passage strewn with silverware and ceramic shards, that heart-shaped stone may still shimmer whenever a submersible’s lamp skims the sediment.

RENAULT TYPE CB COUPÉ DE VILLE — $1 Million

Colorado mining heir William Carter brought a brand-new burgundy Renault onto the Titanic, intending to cruise Manhattan in European style. The car was one of the very first with an electric starter — technology so new it turned heads on the Southampton quay. Carter survived in Lifeboat 4, but his limousine now lies in a “garage” of collapsed deck beams, tires long rotted, brass fittings coated in a thin patina. Classic-car experts peg its theoretical auction value at roughly $1 million; if ever raised and stabilized, it would become the single most storied automobile on Earth.

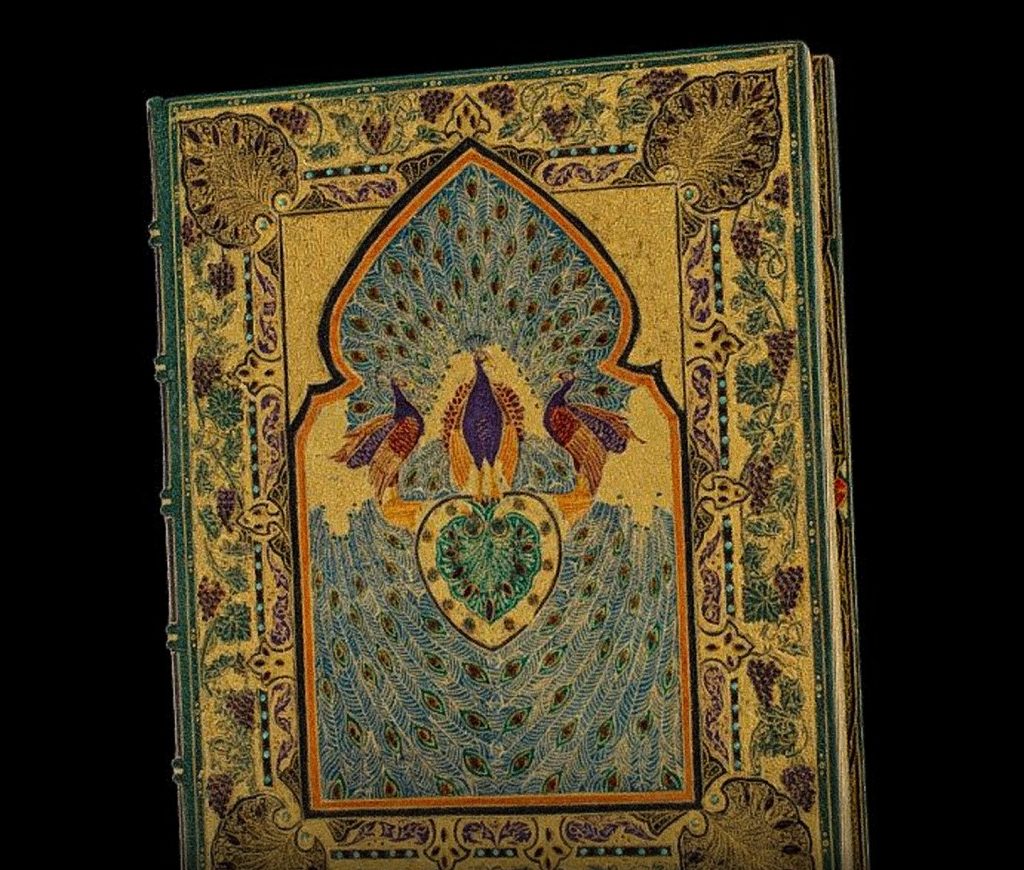

JEWELED RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM — $1.3 Million

Bound in peacock-blue Morocco leather and crusted with nearly two thousand gems, Sangorski & Sutcliffe’s jewel-encrusted Rubaiyat was already infamous for a string of mishaps. The Titanic copy, intended for display in New York’s Grolier Club, vanished with the ship, perpetuating the so-called “Great Omar” curse that haunted every lavish binding the firm attempted. Conservators estimate its current worth at $1.3 million, but bibliophiles argue the manuscript’s legend outshines any price tag. If divers ever retrieve even a single jeweled page, it would rewrite book-collecting lore overnight.

HARBECK’S 110,000-FOOT FILM REELS — $1.6 Million

Early filmmaker William Harbeck boarded with a massive trove of nitrate stock, eager to create the definitive travelogue of a floating city. His silent footage captured Europe’s last pre-war spring, but the raw reels never reached a projector. Specialists in archival cinema estimate the historical value of those scenes at $1.6 million — not for the celluloid itself, but for the unrepeatable moments trapped inside: children scurrying along Southampton pier, stewards polishing brass in First Class, perhaps even a sweep across the Dining Saloon on that final Sunday lunch.

DIANA OF VERSAILLES BRONZE STATUETTE — $2 Million

Among the eclectic pieces owned by industrialist Harry Widener was a bronze lounge figure modeled after the Louvre’s Diana of Versailles. Unlike the ship’s delicate porcelain, bronze tolerates pressure and salt; remote sonar has revealed several human-shaped shadows resting near Cargo Hold B. Maritime historians believe one of them could be the goddess, valued today at around $2 million. Should she ever rise again, her bow and quiver would carry not only Greco-Roman mythology but an entirely new chapter of Titanic storytelling.

EXOTIC BIRD-OF-PARADISE FEATHERS — $2.3 Million

Forty-plus wooden crates labeled “Millinery Plumes — Highly Perishable” sat deep in the forward hold. Fashion houses in New York paid top dollar for Birds-of-Paradise, whose iridescent tails crowned hats seen on Fifth-Avenue promenades. In 1912 the shipment was insured for $12,000; conservation biologists assessing legal market equivalents place the lost consignment near $2.3 million today. Because salt water can preserve keratin, fabric experts believe some feathers may still hold a ghostly sheen, a last flash of Edwardian fashion amid the wreck’s twilight.

LA CIRCASSIENNE AU BAIN — $3.3 Million

Swedish engineer Mauritz Björnström-Steffansson carried Blondel’s 1814 Neoclassical nude rolled carefully under his arm. He envisioned a tour of New York galleries, perhaps a sale to the Metropolitan Museum. Instead, the canvas — insured for a then-jaw-dropping $100,000 — now floats somewhere between crushed steamer trunks and fractured bottles of French wine. Paint analysts suggest its pigment layers may have adhered to the inner hull plates, effectively turning steel into a ghostly gallery wall. Even half-intact, the piece would fetch north of $3.3 million.

CARDEZA’S TRUNKS & CRATES — $5.8 Million

No collection speaks to Gilded-Age opulence like the luggage of Philadelphia heiress Charlotte Cardeza: fourteen Vuitton trunks, twenty handbags, jeweler’s chests, cases of sable, ermine and chinchilla, plus two cedar crates of fine china — the manifest runs for pages. Modern appraisals tally the lost wardrobe at roughly $5.8 million, a sum that barely hints at sentimental value. Divers have recovered monogrammed hat-box hinges and a lone diamond stickpin nearby, but the bulk remains buried beneath fractured cabin floors, locked away as if the Atlantic itself were Cardeza’s private vault.

Why Dollar Signs Cannot Measure Wonder

Adding these objects end-to-end from $600,000 to $5.8 million creates an alluring staircase of numbers, yet the real ascent is emotional. Each artifact is a rung leading back to April 1912 — a night that refashioned human hubris into humility. The necklace evokes a socialite’s courage; the bronze Diana, a scholar’s love of antiquity; the Renault, the thrill of modern engineering; the plumes, the unexamined cost of beauty; the jeweled Rubaiyat, mankind’s compulsion to adorn wisdom with luxury.

I once watched live ROV footage of the Titanic’s bow while standing on the deck of a research ship in the North Atlantic. On a monitor the remotely-operated lights caught a swirl of white particles. For a second the pilot thought it was paper — perhaps a page from the Rubaiyat. It proved only sea snow, but my heartbeat thumped like propeller blades. That is the power these relics hold. Whether they emerge into museum glass or dissolve entirely, their stories keep the ship alive in collective memory.

Money counts, yes, but wonder counts more. The ocean continues to guard that wonder in absolute darkness, promising surprise to anyone daring (or foolhardy enough) to seek it. Until then we list the treasures, price them, order them from smallest fortune to greatest, and dream — the way passengers once dreamed beneath crystal chandeliers — of what might surface next from the cold, eternal night.