THE FASTEST THINGS HUMANS HAVE EVER CREATED

Toyota Corolla — 117 mph

Everyone makes jokes about the Corolla, and yet this humble car is where the story of speed really begins for most of us. It isn’t built to shatter records; it’s built to work every single day. Top speed around 117 mph, depending on the model year and engine. That’s hardly headline‑grabbing, but it’s a useful baseline. Stand on a freeway overpass and watch a sea of practical cars move like a river. Speed, here, is normal life made easier. The Corolla reminds me that progress doesn’t always look like a rocket launch. Sometimes it looks like a reliable commute, quietly stacking millions of safe miles until the extraordinary is possible.

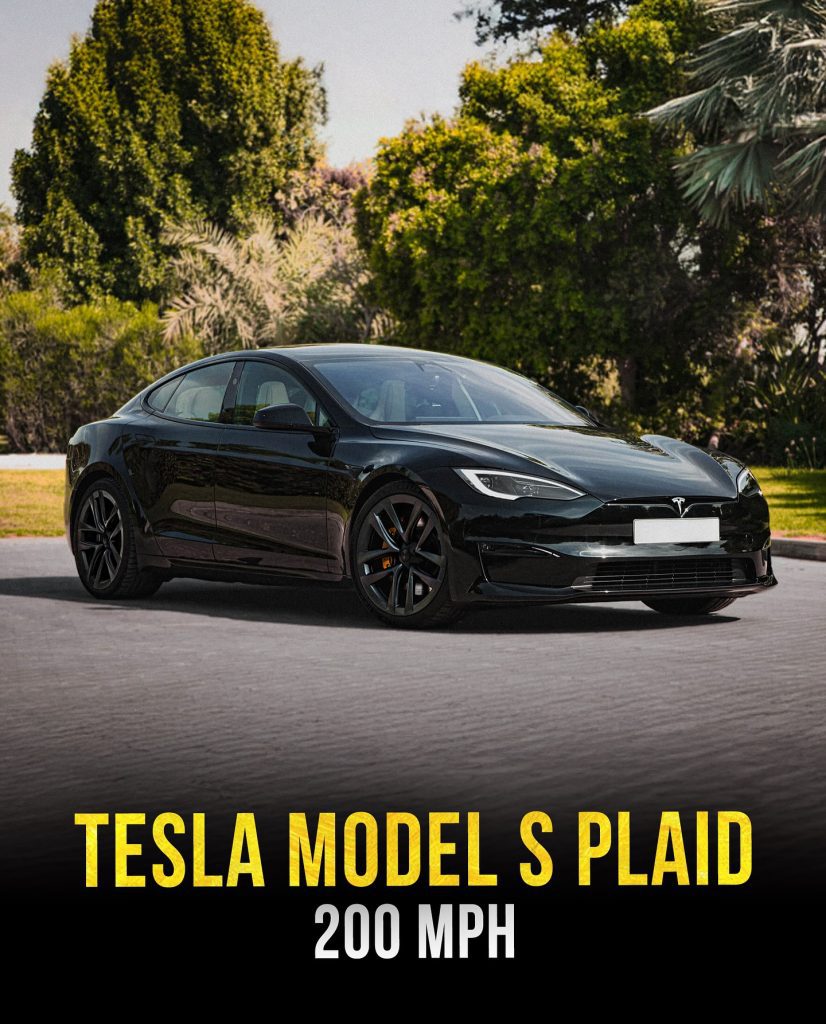

Tesla Model S Plaid — 200 mph

Now move the slider. You press the accelerator in a Tesla Model S Plaid and the cabin tilts the way a roller coaster does when it leaves the station. It’s not just the 200 mph top speed; it’s how quickly it sprints there. Electric torque feels different, like you skipped a page in the physics book. I love that this kind of acceleration can also be almost silent—no roar, no drama, just a quick step into the future. It’s a reminder that “fast” is changing shape, moving from fuel to electrons, from noise to whisper.

Bugatti Chiron Super Sport — 304 mph

There’s a clip of the Chiron Super Sport streaking across a test track at 304 mph that never gets old. You don’t so much watch it as feel it. The scenery turns to watercolor, and the speedometer climbs into territory most of us only know from video games. Even with all the footnotes—one‑way run, special track tires—the symbolism is huge. A car with plates, mirrors, and air conditioning touched a speed that was once reserved for experimental craft. That says something about the engineering curve of our time. We’re squeezing drag, heat, and stability problems that used to belong to aerospace and solving them for something you can park.

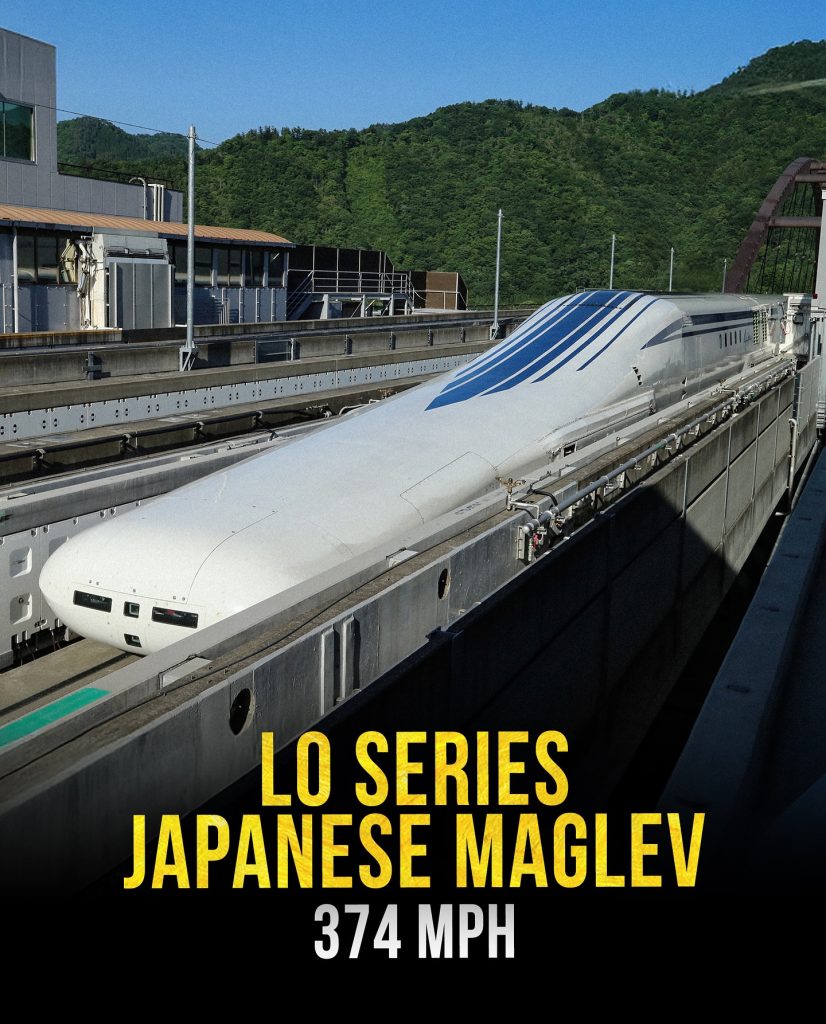

L0 Series Japanese Maglev — 374 mph

Trains are my favorite way to measure a country’s confidence. The L0 Series maglev doesn’t just go fast; it floats. Superconducting magnets lift the train off the guideway so there’s no wheel‑rail friction, which means speed is limited by aerodynamics and power, not steel grinding on steel. Test runs at about 374 mph look unreal—like the future borrowed a track in the present. The beauty of it is that the ride is smooth enough to sip coffee. That’s the hidden promise of speed: not a thrill ride, but time returned quietly to your day.

Boeing 757 — 525 mph

Commercial jets are the unheralded champions of fast. A Boeing 757 cruises in the mid‑500s mph, sometimes more with tailwinds, and does it for hours while six miles up, where the earth looks like a map and cities slide into view with the grace of a turn of the page. This is the kind of speed that reshaped the planet. A grandmother can leave Dublin after breakfast and hug her grandkids in Boston by lunch. Deals, friendships, and ideas fly at 525 mph as if that were always a normal speed. It wasn’t. We made it normal.

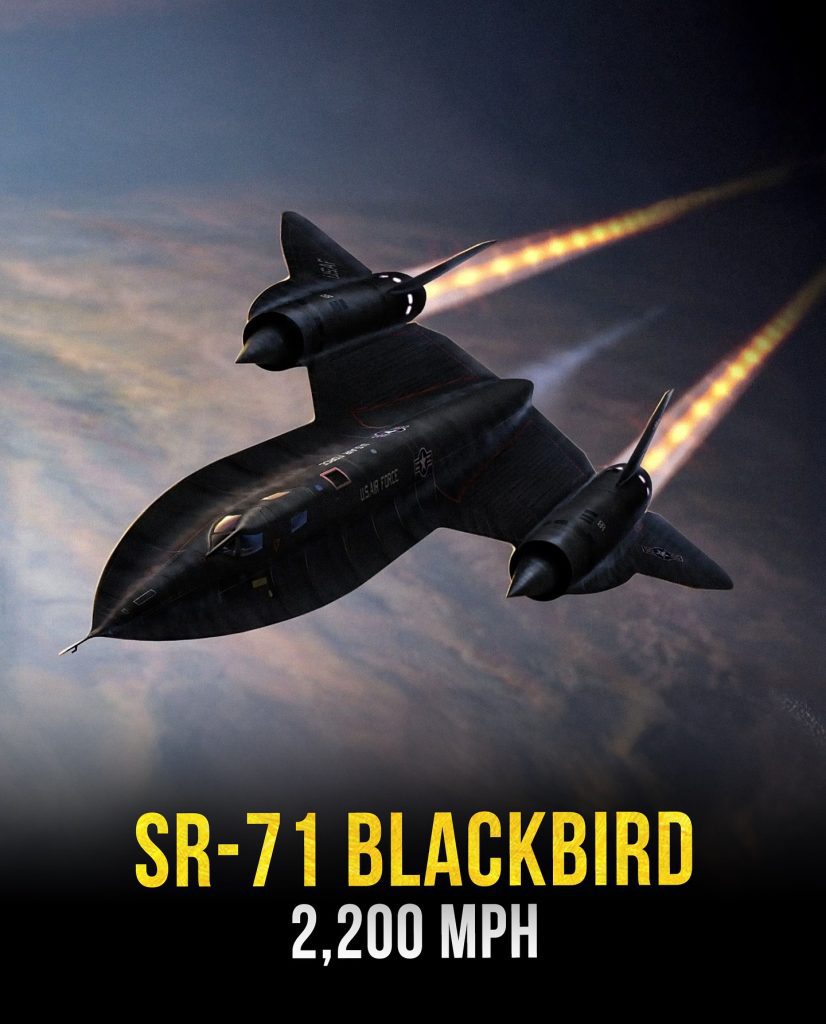

SR‑71 Blackbird — 2,200 mph

Every time I see the SR‑71 in a museum, I walk around it slowly. The edges look like shadows. The skin is black because at Mach 3‑plus it gets so hot that paint isn’t decoration—it’s protection. Officially, the Blackbird’s speed record sits just over 2,190 mph, but everyone knows it was designed to go faster when it had to. It outran threats by simply being beyond reach. There’s poetry in that: sometimes the safest place is not behind a shield but ahead of the danger, so far ahead it can’t touch you.

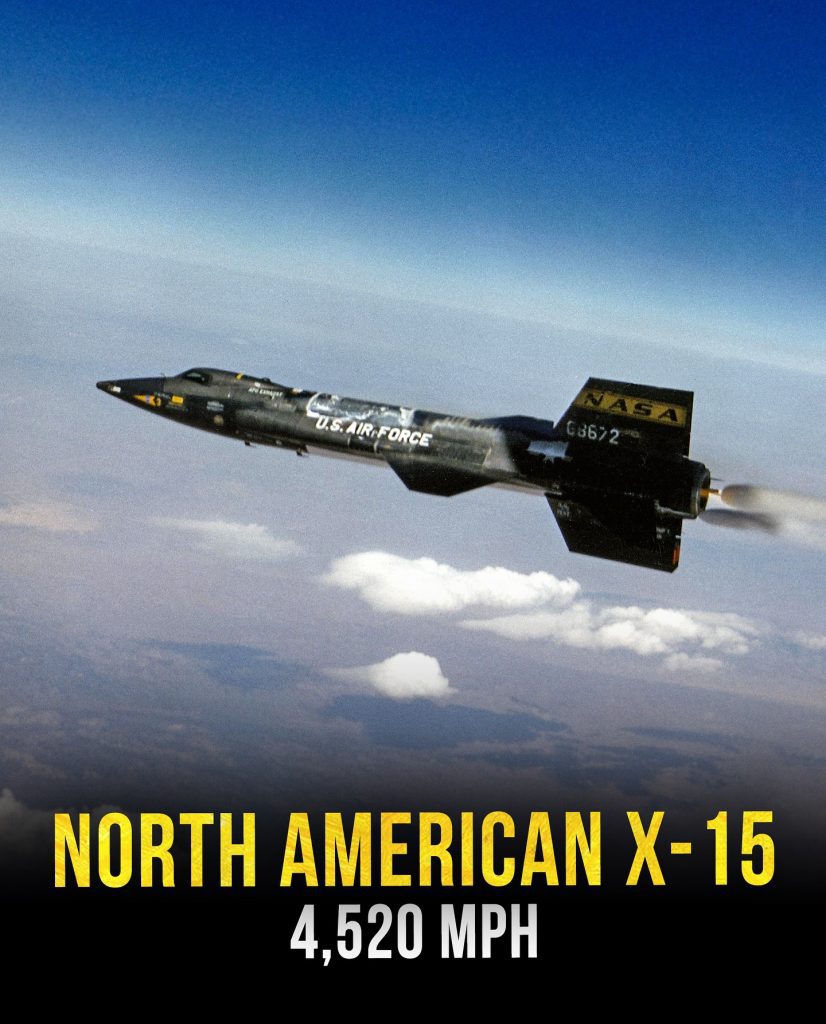

North American X‑15 — 4,520 mph

If you’ve never gone down the rabbit hole of X‑15 footage, treat yourself. It was a rocket with wings, air‑dropped from a B‑52, lighted like a match, and flown by test pilots who combined astronaut grit with fighter‑pilot reflexes. The speed record—about 4,520 mph, or Mach 6.7—still stands for crewed aircraft. The numbers are staggering, but it’s the attitude I love most: Try. Measure. Try again. The X‑15 taught engineers how to fly at the edge of space and taught pilots how to think in dots, because at that speed, the horizon moves in steps.

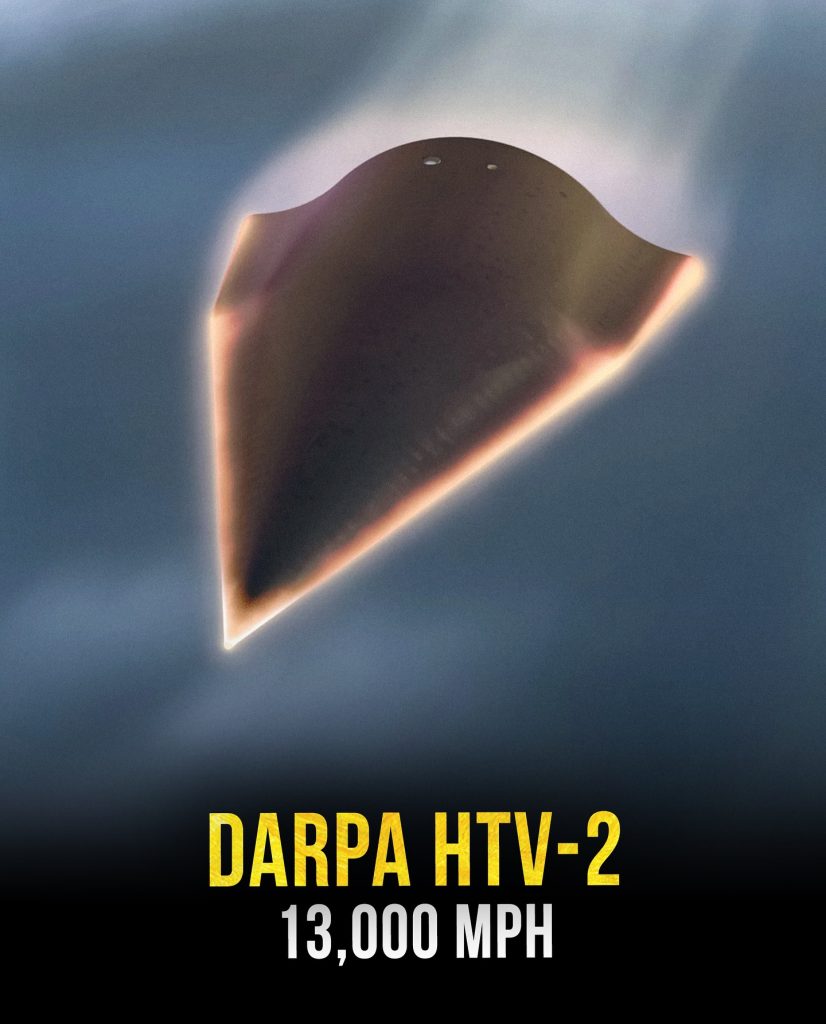

DARPA HTV‑2 — 13,000 mph (reported)

The HTV‑2 looks like a steel arrowhead, built to fall from the sky and then glide at hypersonic speeds. Reports put its peak around 13,000 mph—Mach 20—in short, terrifying bursts. It wasn’t a passenger plane or a weapon in service. It was a question asked at extreme speed: can we guide and survive controlled flight at twenty times the speed of sound? The answer was messy and partial. Flights ended early. Sensors burned. But every scorch mark was data. This is how the frontier moves—two steps forward, one sideways, another forward, until the wild numbers become routine.

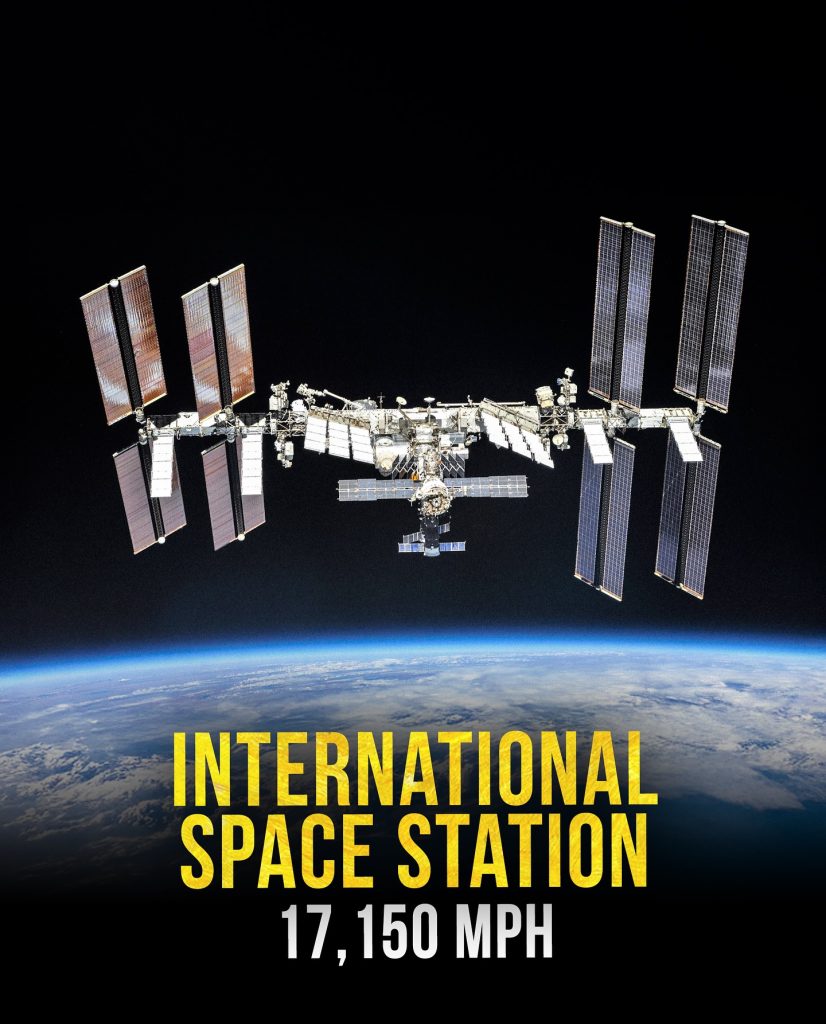

International Space Station — 17,150 mph

Speed in orbit is a different animal. The International Space Station circles Earth roughly every ninety minutes at about 17,150 mph. What amazes me is how calm it looks from inside. Astronauts float through modules, fix water recycling systems, conduct biology experiments, and film sunrises that smear across the blue curve below. That kind of steady, domestic speed makes me smile. You can travel five miles a second and still need to find the duct tape. You can be moving at 25 times freeway pace and still remember to water the lettuce in the space garden.

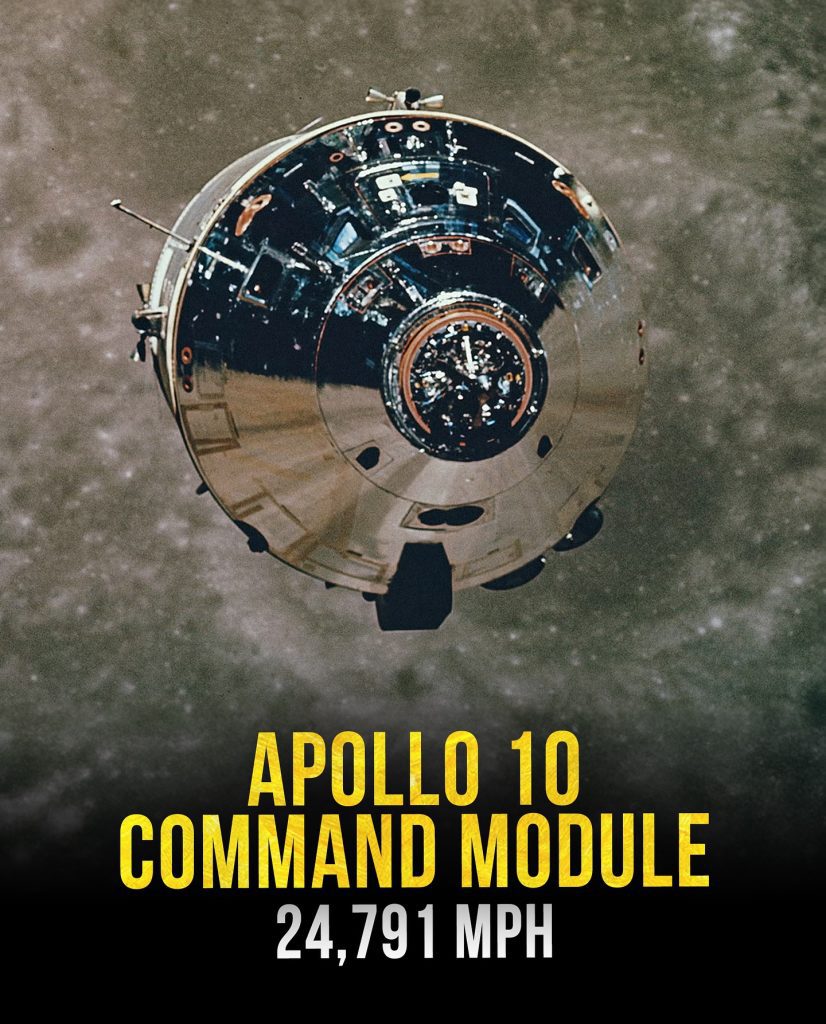

Apollo 10 Command Module — 24,791 mph

Apollo 10 was a dress rehearsal for the first Moon landing, and its return to Earth produced the fastest crewed re‑entry speed on record, about 24,791 mph. Imagine riding inside a bell as it hits the atmosphere so hard that surrounding air turns to plasma, radio goes quiet, and the heat shield earns its paycheck. The thing about that number is the context: these were people in seats, looking at checklists, trusting calculations scratched out on paper and punched into computers with less power than a wristwatch. They hurtled home faster than any humans before or since. “Fast” becomes “courage” at that point.

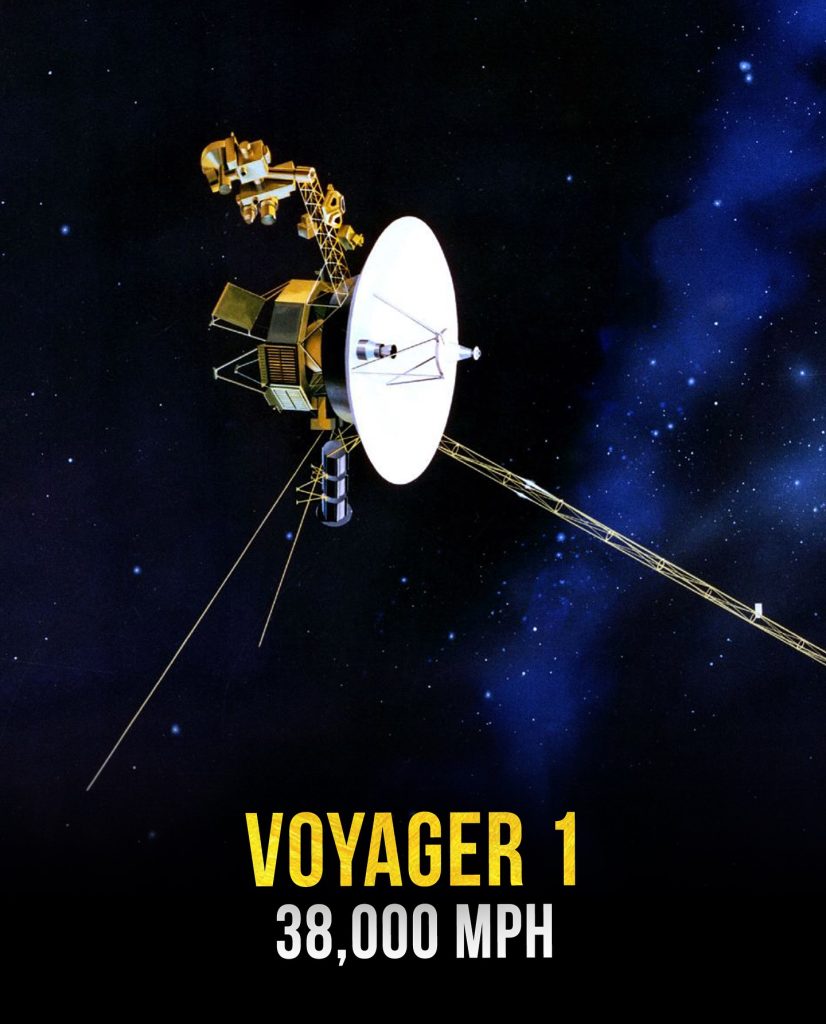

Voyager 1 — 38,000 mph

Voyager 1 is the quiet champion. Launched in 1977, it used gravity like a slingshot and now coasts through interstellar space at about 38,000 mph relative to the Sun. That speed is not fiery; it’s patient. The little spacecraft just keeps going, long after the headlines, long after the cameras on its bus‑sized cousins turned to look elsewhere. When I read updates about Voyager’s faint heartbeat—still sending data across a gulf so large it takes light itself many hours to cross—I think about endurance as a form of speed. It’s the speed that outlasts us.

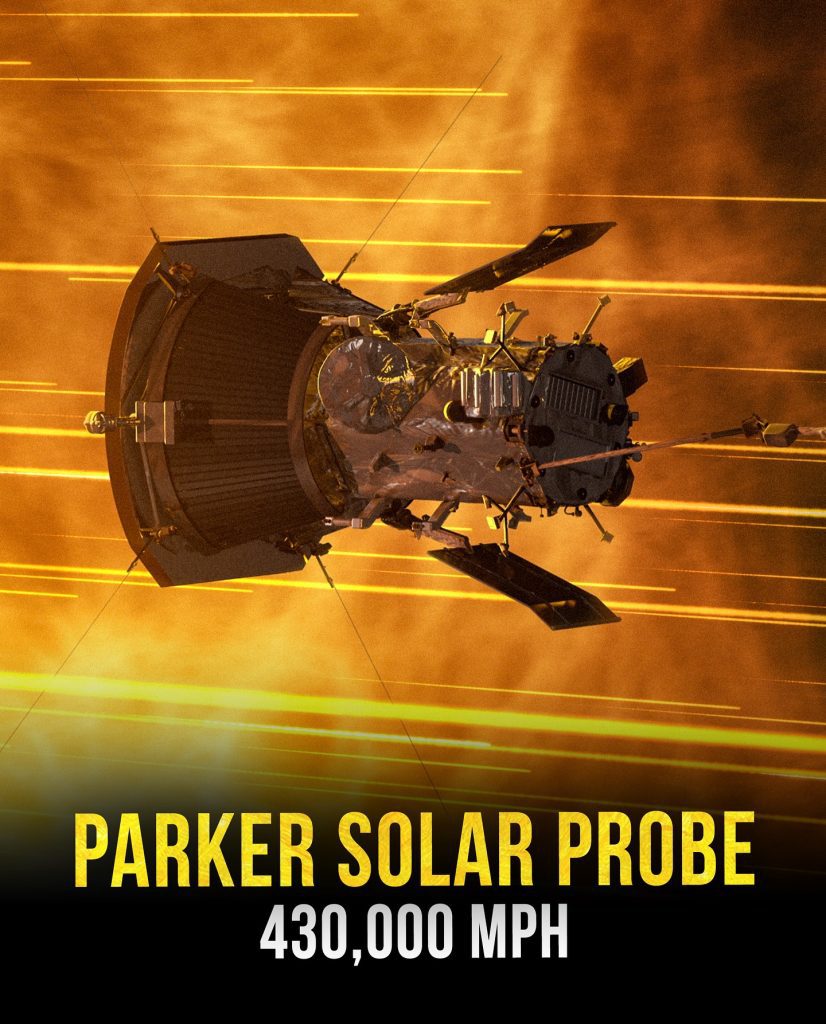

Parker Solar Probe — about 430,000 mph

And then there’s the champ. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe dives toward the Sun again and again, stealing a little more speed each time from a dance with Venus. At perihelion—its closest approach—it is the fastest human‑made object ever, moving at roughly 430,000 mph. The numbers barely make sense: at that pace, you could cross the United States in about twenty seconds. The challenge isn’t only speed; it’s surviving the Sun’s furnace. The probe carries a white heat shield that shrugs off temperatures that would melt most metals, while instruments peek around the edge to taste the solar wind. I love that the fastest thing we’ve ever built is also one of the most patient. It circles, learns, circles again, getting closer to the star that powers everything we love about daylight.

Why lining them up like this matters

It would be easy to treat this list as a scoreboard and move on. But putting these speeds in order tells a deeper story about the kinds of problems we know how to solve. On the ground, drag and traction define the fight; the Chiron wins by slicing air and planting rubber without lifting off. On rails, friction is the villain; the maglev floats over it. In the sky, combustion and materials science rule; the X‑15’s skin glowed with the effort. In space, the trick is gravity itself—how to steal it, bend it, and use it without burning up. The ISS holds speed steady; Apollo rode it home. Voyager stores it for decades. Parker turns it into a dare at the edge of a star.

The other reason I love this lineup is that it’s so human. The Corolla is there because most of us meet speed in errands, not experiments. The Tesla is there because the future sneaks in through updates as well as launches. The Bugatti is there because we can’t resist trying to break our own limits. The maglev is there because comfort matters, too. The 757 is there because the world shrank to the size of a day trip. The SR‑71 and X‑15 are there because courage has always sat in the cockpit. The HTV‑2 is there because science is a verb, and sometimes verbs tumble. The ISS is there because speed can feel like home. Apollo 10 is there because falling back to Earth is its own kind of ascent. Voyager is there because every generation needs a ship in the dark. And Parker is there because, sooner or later, we point our fastest machine straight at the fire and learn something we couldn’t learn any other way.

If there’s a moral hiding in all these miles per hour, maybe it’s this: speed is never just about motion. It’s about imagination keeping pace with responsibility. It’s about how we treat the planet while we hurry across it, how we share the benefits of the machines we build, how we make sure “faster” also means “better” for the people who rarely get to ride up front. The numbers will keep climbing; they always do. But the story of speed will stay human as long as we keep asking, with each new record, not just “how fast,” but “what for.”