NORWEGIAN PRISONS COULD PASS FOR GREAT HOTELS

The first time I stared at a photo from a Norwegian prison, I thought someone had mislabeled an interior design catalog. Sunlight poured across pale wood floors. Chairs in warm colors sat next to wide windows that framed a courtyard with trees. A second photo showed a single room with a bed, a desk, shelves, a small wardrobe, and a door to a private bathroom. No metal bars, no cinderblock gloom. The place looked calm, almost tender, like a college dorm that had learned to whisper. If you’ve only ever seen the tough-on-crime aesthetic—gray walls, constant noise, a hard corner on every surface—these images feel like a trick of the camera. But the more time I spent learning about Norway’s approach, the more the rooms made sense. What looks soft is actually a deliberate strategy with a simple idea at its core: the punishment is the loss of liberty, nothing more. Life inside should resemble life outside as closely as security allows, because almost everyone is going home someday, and the system’s job is to make that homecoming safer for everyone.

That principle has a name in Norway: normality. It sounds gentle, but it’s a demanding standard. It means daily routines that copy the ordinary world. It means lessons with real teachers from the public school system, not a walled‑off curriculum that stops at the gate. It means healthcare delivered by the same regional providers people will use when they’re released. It means libraries staffed the way public libraries are staffed, and chaplains who serve both inside and outside. Officials call this the “import model,” and on paper it reads like a logistical headache. In practice, it shortens the distance between prison and community so release day isn’t a cliff. A person inside learns to navigate the same systems they’ll rely on outside, sometimes with the same professionals guiding the handoff. There’s less awkwardness, less paperwork shock, less of that cold feeling of starting from zero.

Walk into Halden Prison—the most photographed example—and you see how the philosophy turns into architecture. Halden is high security, but its rooms are single‑occupancy with doors that shut like a door at home. There’s an en‑suite shower, a small refrigerator in some units, a TV at the foot of the bed, and a window that draws in natural light without bars across the glass. Common areas look like living rooms: sofas, bookshelves, a kitchen where people cook together and clean up afterward. There’s a music studio stocked like a community arts center, and workshops where people learn carpentry, metalwork, or ceramics. The place is intentionally humane, not because anyone forgot what it means to enforce a sentence, but because the designers understood human nervous systems. Light calms. Wood softens. Nature through glass changes the way a day feels. When people feel less threatened, they tend to act less threatening. When staff work in a space that doesn’t grind them down, they have more patience, better conversations, and fewer bad days spiraling into worse nights.

Everything I’ve read about Norway’s officer training matches those rooms. In a lot of countries, correctional training lasts a few months and focuses on procedure. Norway treats the role like a profession with layers: security, yes, but also communication, ethics, psychology, and law. New officers study for two years at an accredited academy and move through long, supervised placements before they take on full responsibilities. The job still includes firm boundaries and non‑negotiable rules. What changes is the posture. Officers are trained to talk like neighbors who are there to keep order and also to coach people back into community life. That sounds idealistic until you see it in motion: an officer and a resident playing a few minutes of volleyball; a quiet check‑in at a desk; a nudge to finish an assignment before dinner. The everyday tone is human, not hostile. That doesn’t replace security. It sits on top of it.

Bastøy Prison, the open‑security prison on an island south of Oslo, shows how the same principles look when people are closer to release. Photos of Bastøy often go viral because the setting is undeniably beautiful: tidy timber houses, a shoreline that changes with the light, and a rhythm of days that looks like a small town. Men live in shared houses, cook meals, go to classes, and work on the island. There are rules, curfews, and consequences. There have been the occasional walk‑aways, and when trust is broken, transfer back to higher security is swift. But the point of Bastøy is practice—practice being a neighbor again, with responsibilities that feel like the ones waiting on the other side of the ferry. If you think of release as a bridge rather than a jump, Bastøy is one of the planks.

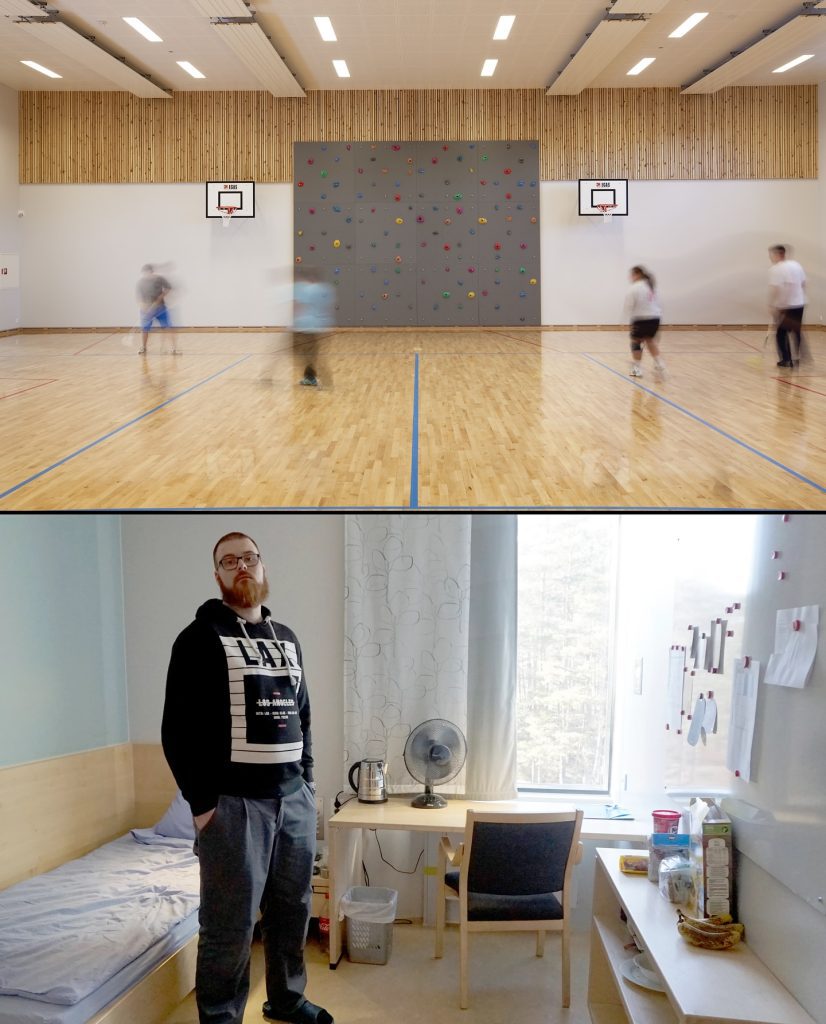

What intrigues me most about the Norwegian model is how ordinary it all looks when you remove the headlines. In the photos I keep revisiting, someone is standing at a stainless‑steel counter slicing cake; another person is wiping down a pan. Elsewhere, men are painting ceramics in a workshop that could be a community learning center. In a classroom, a student is bent over a computer while a teacher leans in and points at the screen. In the yard, a volleyball arcs over the net while an officer shifts into position. If you didn’t know you were looking at a prison, you might call it a campus. The point is not to pretend the fence isn’t there. The point is to rehearse ordinary life inside it so the skills don’t evaporate.

Of course, none of this means Norway is naive about risk or crime. Halden’s perimeter is real. Doors lock. There are counts and searches and consequences. Staff talk candidly about danger and tension. The difference is that the system doesn’t use deprivation as its primary tool. The harshness is the sentence itself—the time away from family, the loss of movement and choice. After that, the system spends its energy on nudging people toward the skills and habits that make communities safer: getting up on time, cooking and cleaning, finishing a class, practicing a craft, showing up for a shift, talking things out instead of letting a small conflict grow teeth. If you raise an eyebrow at a flat‑screen TV, consider what you’re seeing in the background: a structured day, a shared space with rules, a normal conversation that will be repeated, in some form, for the rest of a person’s life.

People often ask whether it “works,” and the most honest answer is also the simplest: fewer people come back. Measured by reconvictions, Norway’s rates are among the lowest reported anywhere. The exact percentages depend on the time window and the study, but the direction is steady. When the everyday environment aims at ordinary life, more people carry ordinary habits out the gate. That outcome is not just good for the person who served the sentence. It’s good for the neighbor who doesn’t lose a bike, the shop owner who doesn’t lose sleep, the child who doesn’t lose a parent to another arrest, the officer who doesn’t spend a career marinating in conflict. Humane design is not a luxury when you count all the costs.

It’s tempting to flatten this into a meme: “Norway puts people in hotel rooms.” That line travels fast online because it’s easy and because the photos are so alluring. But it misses the hardest, least glamorous part of the work: the planning. The import model takes coordination. The officer college takes time and money. The architecture takes intention. The daily routine takes stamina from everyone involved. None of it is magic. Norway is smaller than many countries and has the budget and political will to fund a long, steady experiment. That context matters. Copy‑and‑paste rarely works in public policy. But principles do travel, and pieces can be adapted. You can bring in natural light and calmer color palettes. You can contract with outside educators. You can give officers more training and support. You can build a step‑down path that treats release as a process, not a sudden drop.

When I look at the images you sent—sunlit dayrooms, tidy single rooms, a gym floor with a climbing wall, a studio table covered in brushes and molds—I don’t see indulgence. I see a place trying to keep people’s nervous systems in the range where learning happens. I see officers who are trained to be steady models in a job that eats away at steadiness. I see a system willing to say out loud that the person in front of you, no matter what brings them there, is almost certainly going to be someone’s neighbor again. The right question is not whether a tidy room is too nice for someone who broke the law. The right question is whether the room, and the routine around it, help produce a better neighbor. Norway’s answer has been consistent for years, and the track record backs it up.

So yes, the photos look like a boutique hostel brochure. The rooms could pass for hotel rooms in a pinch. But behind every warm light bulb and every pine plank is a serious bet: treat people the way you want them to act, and many will rise to meet the expectation. Build in dignity, and you reduce the need to fight for it. Keep the outside world at the table, and the transition back won’t feel like a cliff. If that approach ends up looking beautiful in pictures, maybe that says less about “softness” and more about our hunger for places that make us better versions of ourselves—even when those places have walls, counts, and keys.